During a routine site walkthrough at a sprawling petrochemical complex a few years ago, I stopped a team of fitters preparing to break a flange on a high-pressure line. On the surface, they had their permits; they were wearing their hard hats and impact gloves. But when I looked closer, I saw the real story: the scaffolding they were standing on had loose clamps (physical hazard), the line hadn't been fully purged of benzene (chemical hazard), and the lead fitter was visibly exhausted from a double shift (psychosocial hazard). We stopped the job immediately.

That moment highlights a critical truth in our profession: hazards rarely exist in isolation. Understanding the distinct types of safety hazards isn't just an academic exercise for passing your NEBOSH or OSHA 30 exams; it is the foundation of a robust Risk Assessment and the first line of defense against tragedy. In this article, I will break down the primary categories of hazards I encounter in the field, provide real-world examples from my logbooks, and outline the prevention strategies that actually work when the pressure is on.

What is a Safety Hazard?

In my years of auditing safety management systems under ISO 45001, the most common failure I see isn't a lack of PPE—it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what a "hazard" actually is. I have rejected countless risk registers because the team confused the hazard with the consequence.

In simple, practical terms: A hazard is the source of the danger.

According to ISO 45001:2018, a hazard is defined as a "source with a potential to cause injury and ill health." It is the thing, the condition, or the activity that has the intrinsic potential to hurt someone or damage property.

Hazard vs. Risk: The Critical Distinction

You cannot effectively manage safety if you treat these two terms as synonyms.

The Hazard: The potential source of harm (e.g., a 440V electrical cable).

The Risk: The likelihood of that harm occurring combined with the severity of the injury (e.g., the high probability of fatal shock if the cable is uninsulated and touched).

Field Example: A tiger in a secure steel cage is a hazard—it has the potential to kill. But the risk is low because of the cage. If I enter that cage to clean it, the hazard remains the same, but the risk skyrockets.

In the workplace, our job is to identify the hazard first. If we miss the hazard (the source), we can never calculate or mitigate the risk.

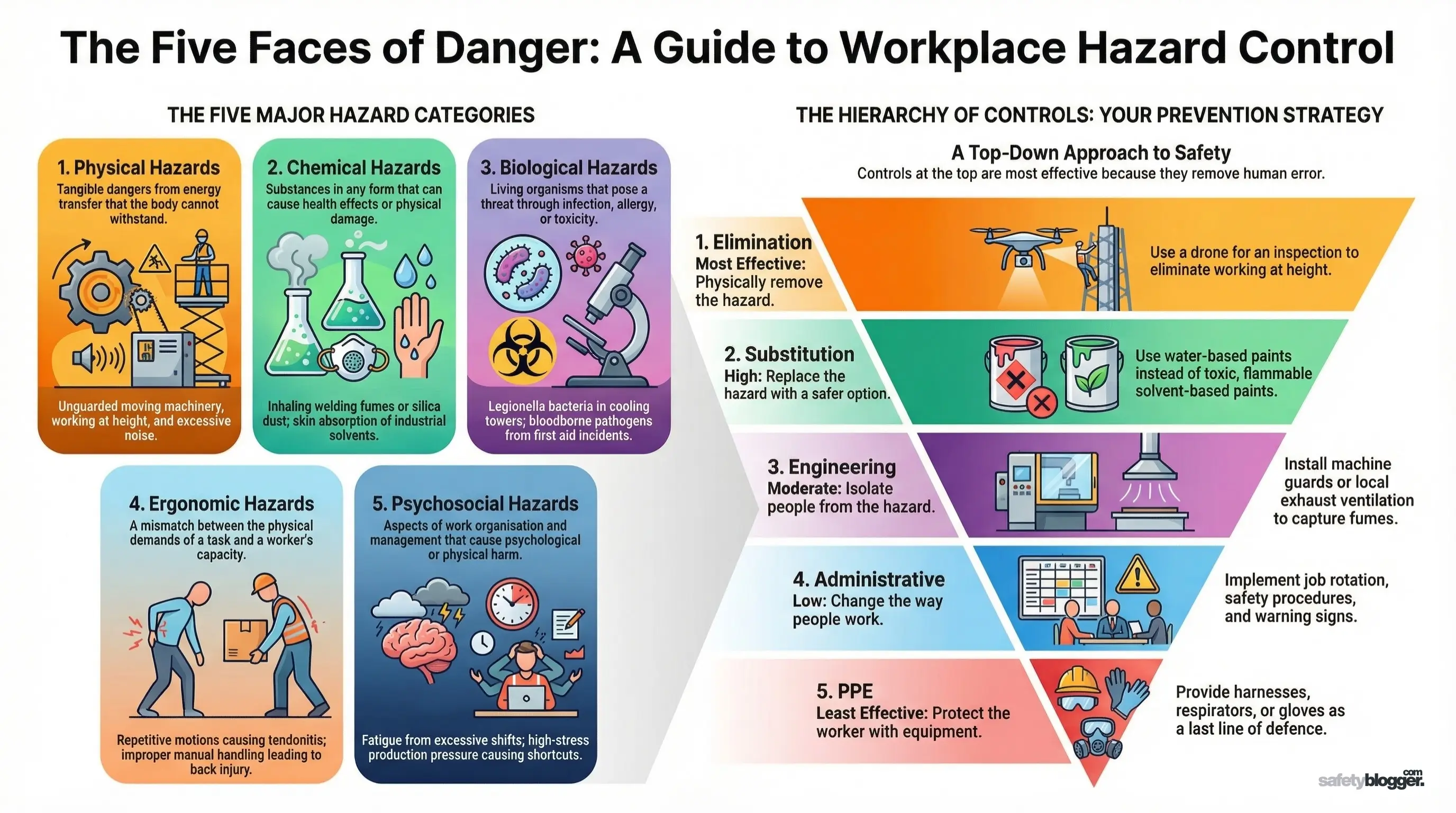

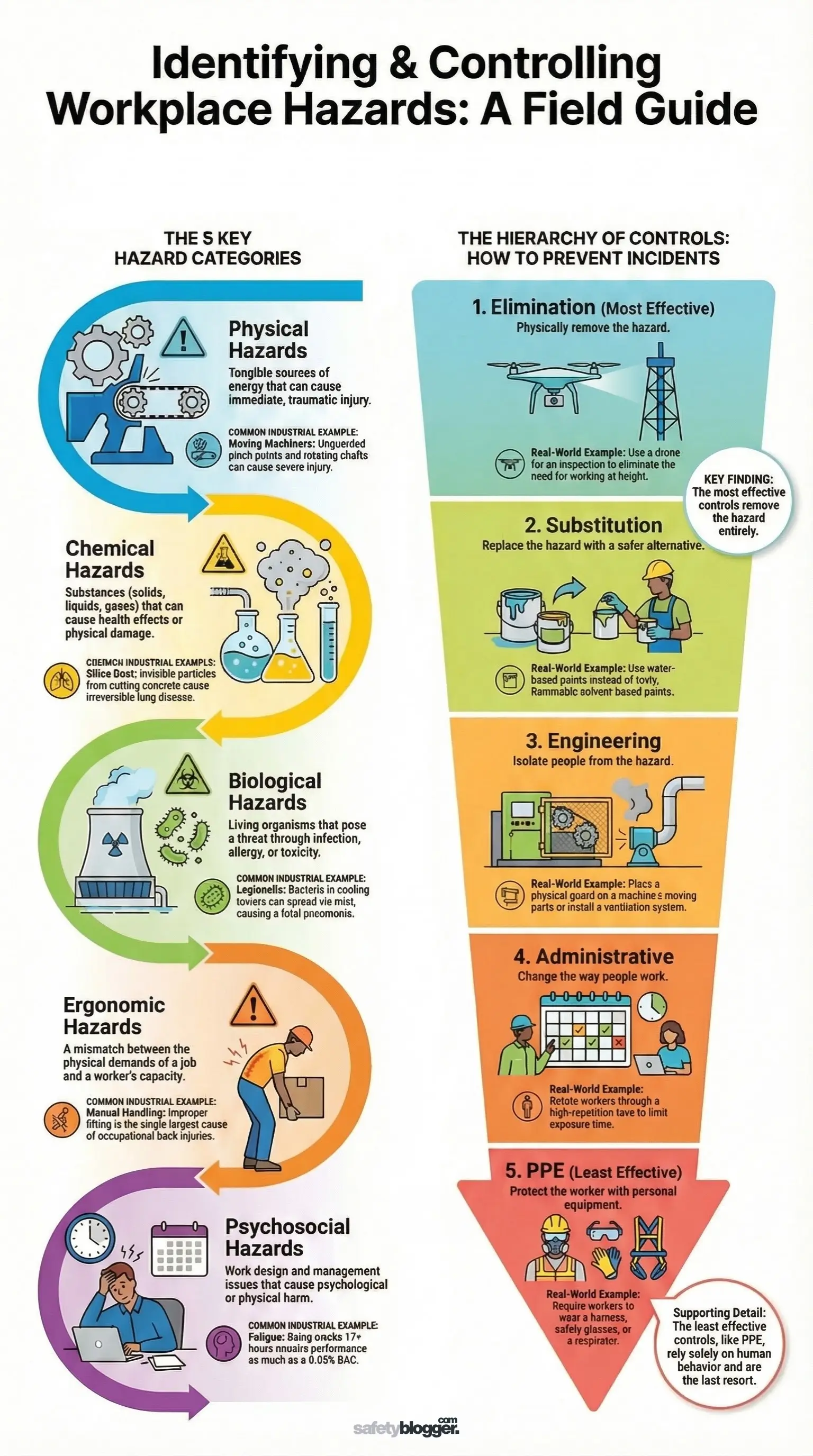

Physical Hazards: The Most Common Offenders

Physical hazards are the most tangible dangers on any site. In my experience as a Risk Management Specialist, these account for the majority of immediate, traumatic injuries. They essentially involve the transfer of energy—kinetic, electrical, or thermal—that the human body cannot withstand.

The danger here is often familiarity; workers get used to the noise of a compressor or the movement of a conveyor belt until they stop perceiving it as a threat.

Working at Height: Gravity is the most persistent physical hazard. I’ve investigated falls from 20 meters and falls from 2 meters; often, the lower falls are more dangerous because workers get complacent and skip the harness.

Moving Machinery: Unguarded pinch points, rotating shafts, and reciprocating parts. I once saw a gloved hand get pulled into a lathe because the operator thought "loose gloves" were safer than no gloves.

Noise: It’s insidious. You don't bleed from noise exposure, but hearing loss is permanent. Anything over 85 dBA requires action, yet I constantly find workers removing earplugs to "hear the radio."

Electricity: From frayed extension cords on construction sites to arc flash risks in substations.

Pro Tip: Never trust a "locked out" machine until you have personally verified the isolation. I carry my own personal padlock for a reason. If the key isn't in your pocket, your life is in someone else's hands.

Chemical Hazards: The Invisible Threat

As an Industrial Hygienist and HSE Manager who has overseen turnaround projects in major petrochemical complexes, I can tell you that chemical hazards are the most insidious risks we face. Unlike a dropped scaffold pole or a tripped breaker, you often cannot see, hear, or even smell a chemical hazard until the damage is already done.

What is a Chemical Hazard?

A chemical hazard is any substance—whether in the form of a solid, liquid, gas, mist, dust, fume, or vapor—that can cause health effects or physical damage due to its intrinsic properties.

In the field, we categorize these into two main buckets based on the GHS (Globally Harmonized System) framework:

Health Hazards: Substances that cause acute (immediate) or chronic (long-term) health issues. This ranges from skin irritation and eye damage to carcinogenicity (cancer-causing) and reproductive toxicity.

Physical Hazards: Substances that threaten physical safety, such as flammables, explosives, oxidizers, or gases under pressure.

The Four Routes of Entry

To manage chemical safety effectively, you must understand how these agents attack the body. In my training sessions, I always emphasize the four routes of entry:

Inhalation: The most common industrial route. Breathing in vapors, dusts, or mists (e.g., breathing in benzene vapors or silica dust).

Absorption: Chemicals passing through the skin or eyes. Some solvents penetrate intact skin and enter the bloodstream directly (e.g., phenol or certain pesticides).

Ingestion: Swallowing chemicals, usually due to poor hygiene—like eating lunch with contaminated hands.

Injection: High-pressure hydraulic leaks or needle sticks forcing chemicals directly into the tissue.

The Backbone of Compliance: GHS and SDS

Managing these hazards is impossible without a rigorous Hazard Communication (HazCom) program. This relies heavily on the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) and strict adherence to Safety Data Sheets (SDS).

Pro Tip: I never let a contractor bring a new chemical on site without seeing the SDS first. I look specifically at Section 2 (Hazards Identification) and Section 8 (Exposure Controls/Personal Protection). If the contractor can't explain Section 8, they don't open the container.

Common Chemical Exposures in Industry

Across many industries, workers are routinely exposed to hazardous chemicals that are often underestimated or invisible. Understanding these exposures—and their real-world health consequences—is critical to preventing chronic illness, acute injury, and long-term occupational disease.

1. Welding Fumes (The Silent Killer)

Welding isn't just about heat; it's about chemistry. When you weld stainless steel, for example, you aren't just dealing with smoke; you are generating Hexavalent Chromium (Cr(VI)).

The Risk: Cr(VI) is a known human carcinogen. I have seen welders who spent years in confined spaces without proper extraction develop occupational asthma and, tragically, lung cancer.

Field Reality: "It's just a quick weld" is the most dangerous phrase in the industry. Even short-term exposure can trigger metal fume fever.

2. Respirable Crystalline Silica (RCS)

In the construction and mining sectors, Silica is widely regarded as the "new asbestos."

The Mechanism: When workers cut, grind, or drill concrete, brick, or stone, they create dust. The visible dust is annoying, but the invisible dust (Respirable Crystalline Silica) is deadly. These microscopic particles lodge deep in the lungs, causing scar tissue (Silicosis), which is irreversible and incurable.

My Experience: I recall stopping a demolition job because the crew was dry-sweeping concrete dust. We immediately switched to wet methods and HEPA vacuums to suppress the airborne hazard.

3. Solvents, Acids, and Corrosives

These are omnipresent in maintenance and cleaning operations.

The Hazard: Many solvents (like Toluene or Xylene) are lipophilic, meaning they dissolve fats—including the natural oils of your skin.

The Incident: I investigated a severe case of dermatitis where a cleaner used a strong industrial degreaser. He wore latex gloves, assuming they were safe. The solvent ate through the latex in minutes, leading to chemical burns and long-term skin sensitization. This was a failure of PPE selection—he needed nitrile or butyl rubber, not latex.

Prevention Strategy: The Hierarchy of Controls

We cannot rely on respirators as a first resort. When I develop a chemical management plan, I follow this strict hierarchy:

Elimination/Substitution (Most Effective): Can we use a water-based cleaner instead of a solvent? Can we use pre-cast concrete to avoid cutting on-site? If yes, we do it.

Engineering Controls: If we must use the chemical, we isolate the worker. This means Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV), fume hoods, or closed-loop systems for chemical transfer.

Administrative Controls: We rotate workers to limit exposure time (reducing the Time Weighted Average - TWA) and enforce strict hygiene practices (no eating/smoking in work zones).

PPE (Last Resort): This is the final barrier. It requires fit-testing for respirators and specific glove selection based on breakthrough times found in the SDS.

Biological Hazards: Living Organisms

When I mention "biological hazards" during site inductions, I usually see eyes glaze over. Most industrial workers assume this applies only to nurses or lab technicians. But in my experience as an Environmental Specialist and HSE Manager on remote projects, biohazards are a sleeping giant in heavy industry.

In the field, we don't just deal with steel and concrete; we deal with living environments. If it’s alive and it can hurt you, it’s a biological hazard.

What is a Biological Hazard?

A biological hazard (or biohazard) refers to biological substances that pose a threat to the health of living organisms, primarily humans. This includes microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi) and macro-organisms (insects, plants, animals) that can cause infection, allergy, or toxicity.

Unlike a chemical spill which is static, biological hazards can grow, multiply, and mutate. A small patch of mold today can be a respiratory crisis next week if left unchecked.

Critical Industrial Exposures

Critical industrial exposures are high-consequence hazards that can cause severe illness or death with little warning if controls fail. These exposures—often biological or environmental in nature—are frequently underestimated because they are invisible, routine, or mistaken for background conditions, yet they demand the same level of rigor as any chemical or physical hazard.

1. Legionella: The Industrial Pneumonia

In power generation and large-scale manufacturing, cooling towers are the heart of the process. They are also the perfect incubator for Legionella pneumophila.

The Science: Legionella thrives in warm, stagnant water (20°C–45°C). The danger isn't drinking the water; it's breathing the mist. Cooling towers generate aerosols (drift). If that water is contaminated, the wind carries the bacteria across the site.

My Audit Experience: I once shut down a cooling system at a textile plant because their biocide dosing pump had failed weeks prior. The logs were faked, but the biofilm slime in the basin told the truth. Legionnaires' disease is a severe, often fatal form of pneumonia. It is not a "bad flu"; it kills workers.

Control: Regular water testing (culture samples), automatic biocide dosing, and drift eliminators are mandatory, not optional.

2. Bloodborne Pathogens & Waste Management

In my early days supervising waste-to-energy plants, I learned quickly that "municipal waste" is rarely just household trash.

The Risk: Workers sorting waste or maintaining sewage treatment plants face exposure to Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and HIV through needle-stick injuries (sharps) or splashes to the eyes and mucous membranes.

First Aid Situations: Even on a construction site, if a worker cuts their hand deeply, the First Aider is instantly exposed to a biological hazard. I always emphasize: Universal Precautions. Treat all blood as if it is infectious.

The "Rat" Factor: In waste handling and excavation, we also deal with Leptospirosis (Weil’s Disease), transmitted through rat urine. I’ve seen groundworkers fall ill simply from wiping sweat from their face after touching contaminated soil.

3. Animal Vectors & Remote Operations

I have spent years managing HSE for pipeline and mining projects in remote locations—from the Australian outback to dense forests. Here, nature fights back.

Venomous Creatures: Snake and spider bites are genuine medical emergencies. On a seismic exploration project, we had to medevac a surveyor after a viper bite. The hazard wasn't just the snake; it was the 4-hour travel time to the nearest antivenom.

Tick-Borne Diseases: In forestry and site clearing, ticks are a massive threat. Lyme disease can debilitate a worker for life with joint pain and neurological issues.

Wild Fauna: I’ve had to write procedures for dealing with bears, stray dogs, and even monkeys on international sites. These animals can carry rabies. The rule is simple: Do not feed, do not approach.

Prevention Strategy: Biological Defense

Controlling biohazards requires a mix of industrial hygiene and medical surveillance.

Engineering Controls: The most effective method. This includes water treatment systems for Legionella, closed-system waste handling, and HEPA filtration for air handling units.

Administrative Controls:

Vaccination Programs: Hepatitis B shots for waste handlers and First Aiders are non-negotiable on my sites.

Hygiene Protocols: Strict "wash up" rules before eating or smoking.

Pest Control: Aggressive rodent and insect management plans.

PPE:

Impermeable gloves (nitrile) when handling waste.

Face shields for tasks with splash risks.

Long sleeves and insect repellent (DEET) for outdoor remote work.

Ergonomic Hazards: The Career-Enders

In the high-adrenaline world of heavy industry, ergonomic hazards are the silent destroyers. They don't generate the flashing lights of an ambulance or the headlines of an explosion, but as an Occupational Health Specialist, I can tell you this: Ergonomic failures retire more good workers than any other hazard type.

We call these Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs). They are not "accidents"; they are the mathematical result of exceeding the human body's design limits over time.

What is an Ergonomic Hazard?

Fundamentally, an ergonomic hazard is a mismatch. It occurs when the physical demands of a task—force, frequency, or posture—exceed the physiological capacity of the worker.

When I investigate a back injury, I rarely find a single "bad lift." I find ten years of bad lifts, poor design, and "toughing it out." The injury is just the straw that broke the camel's back.

The "Big Three" Ergonomic Stressors

Most serious ergonomic injuries can be traced back to three fundamental stressors that quietly overload the human body day after day. When repetition, excessive force, or harmful vibration are built into a task, injury becomes inevitable—not a matter of luck, but of time.

1. Repetitive Motion: The Slow Erosion

The human body is resilient, but it is not a machine.

The Mechanism: Doing the same motion—whether it's twisting a screwdriver, scanning a barcode, or laying a brick—thousands of times a day causes microscopic tears in muscles and tendons. When the rest period isn't long enough for the body to repair these micro-tears, inflammation sets in.

Field Example: I once worked with a team of rebar tiers on a bridge deck. They were making the same rapid wrist twist 8,000 times a shift. By age 35, half of them had Carpal Tunnel Syndrome or severe tendonitis. We introduced automatic rebar tying guns, and the injury rate dropped to near zero.

2. Manual Handling: The Lever Effect

Manual handling is the single largest cause of occupational injury globally.

The Biomechanics: Your spine acts like a lever. When you lift a 20kg box with outstretched arms, the compressive force on your lower lumbar discs (L4/L5) can exceed 200kg due to the torque.

The "Hero" Syndrome: I’ve seen young laborers ruin their backs permanently because they were too proud to ask for a team lift. They think strength protects them. It doesn't. Physics always wins.

Prevention: It’s not just "bend your knees." It’s about keeping the load close to the core (the Power Zone) and eliminating the lift entirely where possible.

3. Vibration: The Nerve Destroyer

Vibration is often ignored until the damage is irreversible. We deal with two types:

Hand-Arm Vibration (HAV): This comes from holding powered tools like jackhammers, grinders, or impact wrenches. Prolonged exposure damages the blood vessels and nerves in the fingers.

The Result: Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS) or "Vibration White Finger." I’ve met veteran road crews who cannot button their own shirts or feel a hot cup of coffee because their nerve endings are dead.

Whole-Body Vibration (WBV): This affects operators of heavy machinery (dump trucks, excavators) driving over rough terrain. It literally shakes the spine apart, leading to chronic lower back pain.

Field Observation: If a task looks uncomfortable to watch, it is likely damaging the worker. "Toughing it out" is not a safety strategy; it's a path to disability.

Prevention Strategy: Fit the Job to the Worker

We do not fix ergonomic hazards by telling workers to "be careful." We fix them by changing the work.

Engineering (The Goal): Use mechanical aids. Vacuum lifters for glass, conveyor belts for materials, and vibration-dampened handles on tools.

Administrative: Job rotation. If a task is high-repetition, no one should do it for more than 2 hours at a time.

The "Power Zone": Design workstations so all work is done between the hips and the chest. If a worker has to work above their shoulders or below their knees, the design has failed.

Psychosocial Hazards: The Human Factor

For decades, the HSE industry operated on the belief that if we fixed the machine and trained the worker, accidents would stop. We were wrong. As a seasoned HSE Director, I have investigated enough "human error" incidents to know that the root cause often lies not in the worker's skill, but in their state of mind.

Psychosocial hazards are aspects of work design, organization, and management that can cause psychological or physical harm. Today, under the framework of ISO 45003, we treat these with the same rigor as a gas leak or a fall hazard.

A distracted, stressed, or fearful worker is a walking hazard. Their situational awareness collapses, and their decision-making slows down.

The "Hidden" Hazards on Site

These hazards don’t come with warning labels or physical barriers, yet they undermine safety more effectively than any broken machine. Fatigue, stress, and toxic workplace behaviors quietly erode attention, judgment, and communication—setting the stage for serious incidents long before a task ever begins.

1. Fatigue: The Impairment Trap

In industries like oil & gas and mining, we operate 24/7. But the human body is not designed for the night shift.

The Science: Studies show that being awake for 17 hours impairs performance to the same level as a Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) of 0.05%. At 24 hours, it’s 0.10%—legally drunk in most jurisdictions.

Field Reality: I recall a crane operator on a remote rig who dropped a load because he "micro-slept" for two seconds. He wasn't lazy; he was on his 14th consecutive night shift without adequate rest breaks. That is a management failure, not an operator failure.

The Hazard: It’s not just lack of sleep; it’s poor shift rotation design disrupting circadian rhythms.

2. Stress and Production Pressure

There is often a silent war between "Safety" and "Operations."

The Conflict: When a Project Manager stands over a crew screaming, "We are burning cash! Just get it done!", they are actively introducing a hazard.

Cognitive Tunneling: High stress causes "cognitive tunneling." The worker becomes so focused on the task (to appease the boss) that they physically stop seeing peripheral risks—like a reversing truck or a changing gas monitor.

The Result: Shortcuts. Safety steps are the first thing to go when time is tight.

3. Bullying, Harassment, and Toxic Culture

Safety relies entirely on communication. If a culture is toxic, communication dies.

The Silencing Effect: I once audited a construction site where the foreman used humiliation as a management tool. The result? When workers saw a loose scaffold clamp, they didn't report it because they were terrified of being yelled at for "slowing down the job." That scaffold eventually failed.

Psychological Safety: To have physical safety, you must have psychological safety—the belief that you won't be punished for speaking up or making a mistake.

Field Truth: A toxic workplace is an unsafe workplace. If your team is afraid of you, they will hide their near-misses. And hidden near-misses eventually become fatalities.

Prevention Strategy: Managing the Mind

We cannot simply tell workers to "cheer up" or "stay alert." We must engineer out the stressors.

Fatigue Risk Management Systems (FRMS): We move beyond simple hours-of-service rules. We use bio-mathematical modeling to design shift patterns that allow for genuine restorative sleep.

Stop Work Authority (SWA): This must be real, not just a poster. Management must publicly reward—not punish—workers who stop the job due to unsafe conditions or confusing instructions.

Just Culture: We shift from a "blame culture" to a "just culture." If a worker makes an honest mistake, we coach them. If the system forced the mistake (e.g., impossible deadlines), we fix the system.

The Hierarchy of Controls: How We Prevent Incidents

In my twenty years of signing off on Permit to Work (PTW) forms and leading ISO 45001 audits, the single most common failure I witness is the "PPE Reflex." This is where a supervisor sees a hazard—say, a noisy generator—and their immediate solution is, "Give the guys earplugs."

This is lazy safety management, and it gets people hurt.

The Hierarchy of Controls is not just a textbook diagram; it is a rigid framework that forces us to think critically. It is an inverted pyramid for a reason: the controls at the top are the most effective because they remove the human factor, while the controls at the bottom are the least effective because they rely entirely on human behavior.

Why the Order Matters: Reliability vs. Effort

When we design a safety system, we must battle the Law of Validity.

Top Tier (Elimination/Substitution): These are "Hard Barriers." They are difficult to implement (often requiring design changes or capital investment) but are 100% reliable. If I remove the noisy generator, you cannot suffer hearing loss.

Bottom Tier (Administrative/PPE): These are "Soft Barriers." They are cheap and easy to implement but highly unreliable. Earplugs only work if they are the right size, inserted correctly, worn 100% of the time, and not removed to talk to a coworker.

In my experience, if your safety plan relies solely on PPE, you are not managing the risk; you are merely documenting it.

Comprehensive Control Strategy Matrix

Below is the framework I use when evaluating Risk Assessments (RA) and Job Safety Analyses (JSA). I challenge my teams to exhaust each level before moving down to the next.

Control Level | Effectiveness & Reliability | Implementation Phase | Description | Real-World Field Application |

1. Elimination | Highest | Design / Planning | Physically removing the hazard from the workplace entirely. This is the only way to achieve "Zero Harm" for that specific risk. | Construction: Pre-casting concrete pillars on the ground to eliminate work-at-height.Electrical: Using 24V DC tools instead of 240V AC to eliminate fatal shock risk.Transport: Using drones for stack inspections instead of sending climbers. |

2. Substitution | High | Procurement / Planning | Replacing the material, machine, or process with a less hazardous one. The hazard remains, but the severity is drastically reduced. | Chemical: Switching from oil-based paints (flammable/toxic) to water-based paints. |

3. Engineering Controls | Moderate | Installation / Operations | Isolating the worker from the hazard. These controls work independently of the worker's behavior (they don't need to "remember" to be safe). | Guarding: Fixed guards on conveyor belts preventing access to pinch points. |

4. Administrative Controls | Low | Daily Operations | Changing the way people work. This relies on training, procedures, signs, and supervision. It fails if the worker is tired, distracted, or complacent. | Rotation: Limiting jackhammer use to 1 hour per person to prevent HAVS. |

5. PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) | Lowest | Daily Operations | Protecting the worker with wearable gear. This does not reduce the hazard; it only places a barrier between the hazard and the body. | Respiratory: FFP3/N95 masks for silica dust (requires fit testing). |

Pro Tip: When you review a Method Statement, look for the "Alibi Logic." If the contractor lists 10 hazards and the control for all of them is "Worker to wear PPE," reject it immediately. That is not a plan; it's a wish.

Conclusion

In my decade of walking sites—from the freezing winds of wind farms to the scorching heat of desert refineries—I have learned that hazards are dynamic. A safe site at 8:00 AM can be a death trap by 2:00 PM if conditions change or focus drifts.

Understanding the types of safety hazards is the first step in a culture of prevention. But remember: paper doesn't save lives; people do. It is our moral obligation to look beyond the checklist, engage with the workforce, and ensure that every control measure we implement is practical, understood, and effective.

Comments

Loading...