I once inspected a newly commissioned conveyor system at a cement plant that looked perfect on paper. The motors were efficient, the throughput was high, and the price was right. However, during the first week of maintenance, we realized the manufacturer had placed the grease points inside the guarding, forcing the mechanic to remove a safety panel while the belt was running just to lubricate the bearings. That single design choice turned a routine task into a potential fatality. We had to shut down and retrofit the entire line at massive cost.

Manufacturers bear a heavy burden that goes far beyond simply fabricating metal or mixing chemicals. They are the architects of the hazards we face in the field. If they fail to design safety into the product, no amount of training or PPE on our end can fully mitigate the risk. This article outlines the specific, non-negotiable health and safety responsibilities of manufacturers—from the initial blueprint to the final disposal—providing you with the knowledge to hold them accountable.

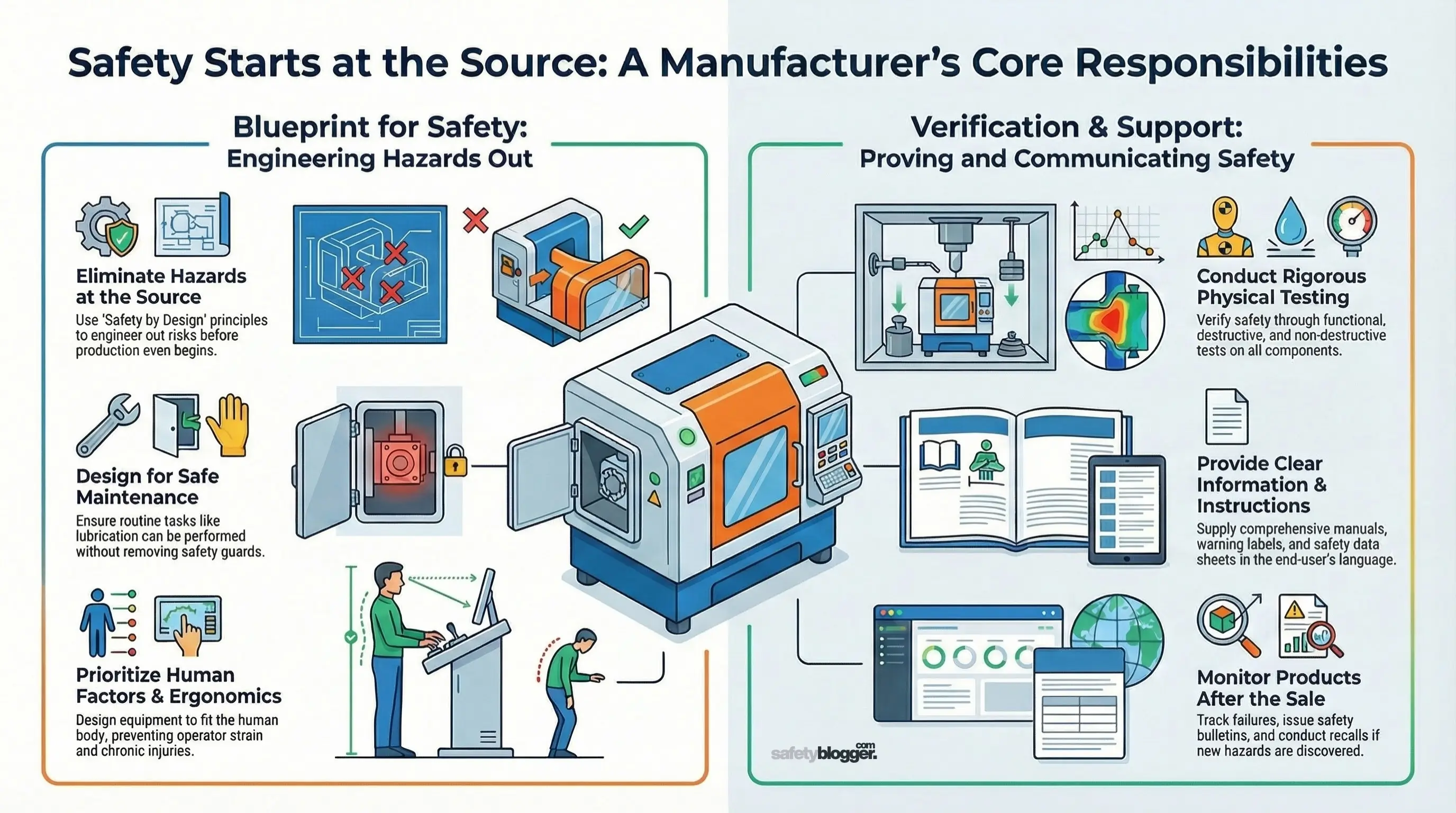

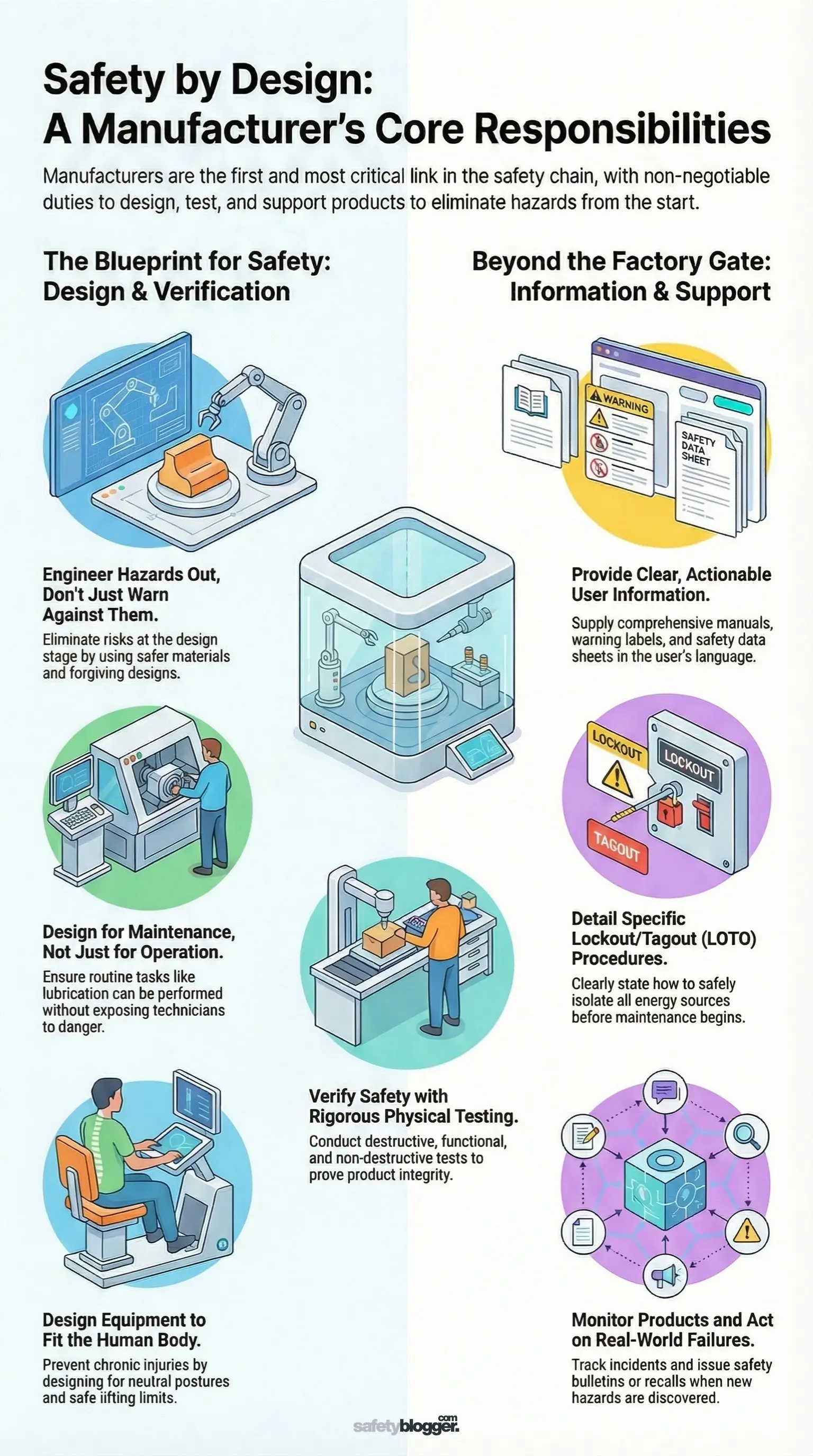

1. Inherently Safer Design (Prevention Through Design)

The most effective way to manage risk is to eliminate it at the drawing board. Manufacturers are legally and ethically bound to apply "Safety by Design" principles, ensuring that hazards are engineered out rather than just warned against. This is the foundation of standards like ISO 12100.

Design processes to operate at lower pressures or temperatures to reduce catastrophic failure risks.

Eliminate pinch points and crush zones by increasing the geometric spacing between moving parts.

Substitute toxic materials or fluids with less hazardous alternatives during the specification phase.

Ensure that failure modes are predictable and safe, such as a valve that fails closed rather than open.

Integrate fixed guarding that requires tools to remove, preventing casual tampering by operators.

Position controls and displays outside of hazardous zones so operators are not exposed during normal use.

2. Rigorous Testing and Quality Assurance

A manufacturer cannot rely on theoretical calculations alone; they must physically verify that their product can withstand the harsh realities of an industrial environment. I look for empirical evidence of this testing during factory acceptance tests (FAT).

Conduct destructive testing on sample batches to verify the breaking strength of materials.

Perform non-destructive testing (NDT) like X-ray or ultrasound on critical welds to detect internal flaws.

Run functional safety tests on all emergency stops and interlocks to ensure they engage immediately.

Verify pressure vessels and piping through hydrostatic testing at pressures higher than operating limits.

Test electrical components for insulation resistance and grounding continuity to prevent shock hazards.

Simulate extreme environmental conditions (heat, cold, vibration) to ensure the equipment does not degrade.

3. Comprehensive Information and Instructions

The equipment is only as safe as the knowledge transferred to the user. Manufacturers are responsible for providing clear, actionable, and language-appropriate instructions that cover the entire lifecycle of the product.

Provide Operation and Maintenance Manuals (O&M) in the local language of the end-user.

Supply Safety Data Sheets (SDS) that fully detail chemical properties, first aid, and spill response.

Mark the equipment with durable, high-contrast warning decals that identify residual risks.

Clearly state the limits of the machine, such as maximum load, wind speed ratings, or duty cycles.

Detail the specific lockout/tagout (LOTO) procedures required to isolate energy sources safely.

Provide detailed lifting plans, including center of gravity and weight, for safe transport and installation.

4. Designing for Safe Maintenance

Manufacturers often design for operation but forget that machines need to be fixed. It is their responsibility to ensure that routine maintenance can be performed without exposing the technician to unacceptable risks.

Locate lubrication points, gauges, and adjusters outside of guarded areas to allow access while running.

Design heavy components with lifting lugs or guide rails to aid in safe removal and replacement.

Provide safe access platforms, walkways, and anchor points for work-at-height requirements.

Ensure confined spaces (like tank interiors) have sufficiently large manways for rescue access.

Eliminate the need for special, non-standard tools that might encourage workers to improvise dangerously.

Design electrical panels with touch-safe components to prevent accidental contact with live busbars.

5. Ergonomics and Human Factors

Workers are not robots; manufacturers must design equipment that fits the human body. Ignoring ergonomics leads to chronic occupational illnesses like musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), which are a massive liability.

Design control panels at heights and angles that prevent awkward bending or reaching.

Limit the weight of manually handled parts to safe lifting thresholds.

Shape handles and grips to keep the wrist in a neutral position during tool use.

Reduce the force required to activate levers, pedals, and wheels to prevent muscle strain.

Design displays and interfaces to be intuitive, reducing cognitive load and the chance of operator error.

Ensure adequate lighting is built into the machine for areas that require visual inspection.

6. Noise, Vibration, and Emissions Control

Health hazards are often invisible. Manufacturers are responsible for minimizing the physical agents that cause long-term harm, such as deafness, nerve damage, or respiratory disease.

Insulate engines and gearboxes to keep noise levels below regulatory action values (typically 80-85 dBA).

Isolate vibrating components with dampers to prevent Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS) in users.

Install local exhaust ventilation ports on machines that generate dust, fumes, or mists.

Seal systems to prevent the leakage of fluids, gases, or vapors into the workplace atmosphere.

Select materials that do not off-gas toxic compounds when heated or stressed.

Provide data on emission levels so the end-user can assess the need for PPE.

7. Supply Chain Traceability

A manufacturer is the single point of accountability for their product, even if they bought parts from fifty different suppliers. They must ensure that every bolt, seal, and sensor meets the safety specifications.

Audit sub-suppliers to ensure they adhere to quality and safety standards.

Maintain a traceability system that tracks which batch of raw materials went into which serial number.

Verify that purchased components carry the necessary certifications (e.g., ATEX/IECEx for explosive atmospheres).

Reject substandard materials immediately rather than allowing them into the production line.

Maintain records of material origin (Mill Test Certificates) for safety-critical structural steel.

8. Post-Market Surveillance and Recalls

Responsibility does not end at the sale. Manufacturers must monitor their products in the real world and take action if unforeseen dangers arise.

Monitor warranty claims and incident reports to identify trends in equipment failure.

Issue safety bulletins immediately if a defect or new hazard is discovered.

Execute product recalls efficiently, locating and notifying all affected customers.

Provide software updates to fix bugs in control systems that could compromise safety.

Maintain an inventory of critical spare parts to prevent users from using unsafe makeshift repairs.

Conclusion

Safety is a chain, and the manufacturer is the very first link. If that link is weak—if the design is flawed, the testing skipped, or the manual unclear—the entire chain fails, often with tragic consequences. As HSE professionals, we must scrutinize our suppliers relentlessly. Do not accept equipment that transfers the risk to your team. Demand the engineering, the documentation, and the integrity that you paid for.

Comments

Loading...