I recall sitting in a boardroom during a Stage 2 ISO 45001 audit for a mid-sized manufacturing firm, staring at a shelf perfectly lined with pristine safety binders. On paper, their Health & Safety Management System (HSMS) was flawless—policies were signed, risk registers were populated, and training matrices were full—yet, just an hour earlier, I had witnessed a forklift operator bypass a critical safety interlock while his supervisor watched in silence. That disconnect is the single most common failure I see in my career: treating an HSMS as a documentation exercise rather than the operational nervous system of the company.

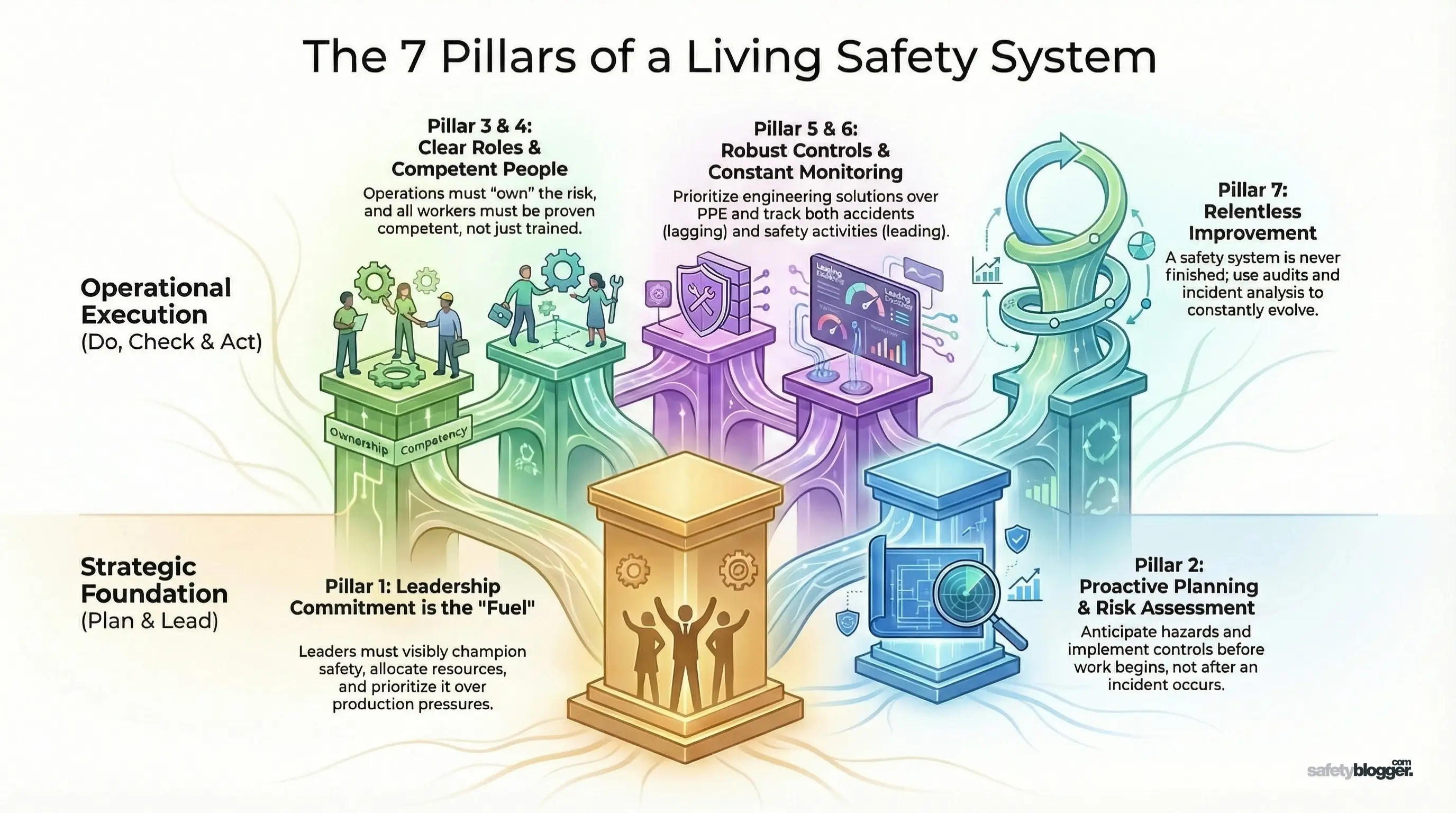

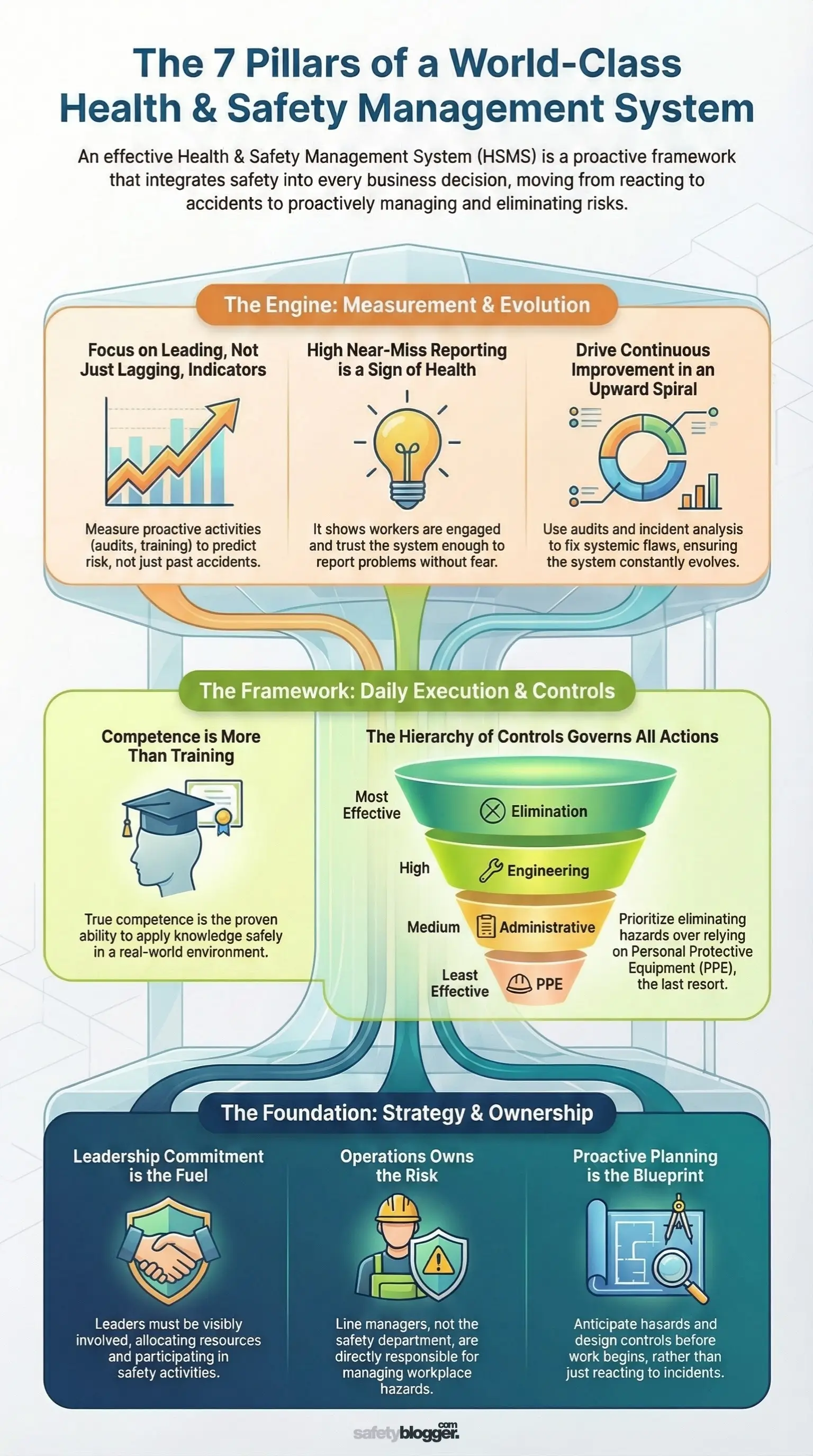

A true Health & Safety Management System isn't just a stack of paperwork or a regulatory shield; it is a structured framework that integrates safety into every business decision, from procurement to production. Whether you are adhering to ISO 45001, OSHA guidelines, or local legislation, the goal remains the same: to move from reacting to accidents to proactively managing risk. In this article, I will break down the seven non-negotiable elements that transform a safety manual into a living, breathing culture that protects workers and ensures business continuity.

1. Policy and Leadership Commitment

Based on my experience auditing heavy industries and corporate boardrooms, this section is arguably the most critical part of any Health & Safety Management System (HSMS). It serves as the foundation—if this part is weak, the entire safety structure will crumble when tested.

Here is a breakdown of what Policy and Leadership Commitment actually means in practice and why it matters:

The Policy (The Promise)

The policy is the formal document, but it is more than just a signature. It is the organization's public declaration of intent.

Statement of Intent: It must clearly state that no job is so urgent that it cannot be done safely.

Regulatory Promise: It commits the company to meeting (and exceeding) legal obligations, not just doing the bare minimum.

Accessibility: It cannot be hidden in a file. It must be displayed on notice boards, included in induction handbooks, and understood by the newest laborer on site.

Leadership Commitment (The Action)

This is where most companies fail. "Commitment" is not about what management says in meetings; it is about what they do when there is a conflict between safety and profit.

"Felt Leadership": This is a term we use to describe visibility. Managers must be seen on the shop floor wearing PPE, following the rules, and correcting unsafe acts personally.

Resource Allocation: Safety costs money. True commitment means approving budgets for better tools, safer machinery, and high-quality training without hesitation.

Active Participation: Leaders should not just read safety reports; they should lead safety committee meetings and participate in incident investigations to understand why things went wrong.

The Consequence of Failure

If leadership does not genuinely care, the workforce will immediately know.

Culture of Fear: If leaders punish mistakes rather than fixing systems, workers will hide incidents.

Production Pressure: If a supervisor sees the CEO ignoring safety to meet a deadline, they will do the same.

System Collapse: Without leadership driving it, the safety manual becomes a "doorstop"—useless paper that nobody follows.

In summary: The policy is the rules of the road, but leadership commitment is the fuel that keeps the car moving. Without the fuel, the car (your safety system) goes nowhere.

2. Planning and Risk Assessment

An effective HSMS relies on anticipation, not reaction. Planning involves looking ahead to identify where the next incident might come from and implementing controls before a worker is ever exposed to the hazard. This element aligns closely with the "Plan" phase of the PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycle found in ISO 45001.

This element is the architectural blueprint of your safety system. It moves the organization from a reactive stance (cleaning up accidents) to a proactive stance (predicting and preventing them).

Key Component | What It Is | Practical Application (The "Real World") |

Proactive Planning | The strategic phase where you anticipate potential incidents before work begins. It aligns with the "Plan" phase of the ISO 45001 PDCA cycle. | Instead of waiting for a worker to cut their hand to buy better gloves, you analyze the cutting task beforehand and engineer a guard so the blade never touches the hand. |

Dynamic Risk Assessment | Treating risk analysis as a "living process" rather than a static document. It must evolve as the workplace changes. | If you replace a manual lathe with a CNC machine, the old 2019 risk assessment is trash. You must re-assess immediately because the hazards have shifted from manual handling to automation risks. |

Hazard Identification | The systematic process of spotting all sources of harm, including physical, chemical, and ergonomic threats. | This isn't just looking for trip hazards. It’s identifying that the solvent used in the cleaning bay causes dizziness (chemical) or that the assembly line height is causing back pain (ergonomic). |

Legal Register | A tracked inventory of all current laws, regulations, and standards applicable to your specific industry. | You need a list that tells you exactly which OSHA or local laws apply to you. If the government lowers the exposure limit for silica dust tomorrow, your register flags this so you can upgrade your masks. |

Objectives & Targets | Setting clear, data-driven goals to measure safety success, rather than vague aspirations. | Don't say "We will try to be safer." Say "We will reduce forklift near-misses by 30% by installing blind-spot mirrors in Q3." This gives the team a concrete target to hit. |

Why This Matters in the Field

If Leadership (Element 1) is the engine of the car, Planning (Element 2) is the steering wheel. Without it, you have a lot of power but no direction, and you will eventually crash.

If you fail to plan: You are constantly fighting fires and paying for injuries.

If you plan effectively: You eliminate hazards at the design stage, which is cheaper, faster, and safer than relying on PPE.

3. Organizational Structure and Responsibilities

This element addresses the "Who" of the safety system. In my experience auditing major projects, the most dangerous organizational structure is one where the entire burden of safety is dumped onto the HSE Department. This creates a "silo" effect where production managers focus solely on output, assuming "the safety guy will catch the hazards."

A functional HSMS destroys this silo. It embeds safety responsibilities into every role, ensuring that safety is treated as a line management function, not a support function.

The Core Philosophy: "Operations Owns the Risk"

The most critical concept in this section is that Line Management (Operations) is responsible for safety, not the Safety Department.

The Logic: The person who assigns the work, controls the budget, and sets the schedule is the only person who can truly control the risk.

The Failure: If a Site Manager says, "Go talk to the Safety Officer" when asked about a hazard, the system is broken. The Site Manager owns that hazard; the Safety Officer is there to advise on how to fix it.

Breakdown of Key Responsibilities

Here is how duties must be distributed to avoid ambiguity:

Top Management (The Architects):

Their role is governance and resources. They are not expected to inspect scaffolds, but they are expected to hold their subordinates accountable. If safety stats drop, they must demand answers just as they would if production stats dropped.

Key Duty: Reviewing safety performance data and providing the budget for improvements.

Line Managers & Supervisors (The Enforcers):

These are the most important people in the safety chain. They are on the floor, watching the work happen. If a supervisor walks past an unsafe act without stopping it, they have just approved it.

Key Duty: Delivering toolbox talks, enforcing PPE rules, and correcting unsafe behaviors immediately.

HSE Department (The Advisors):

We are the internal consultants and the "conscience" of the company. We do not "make" the site safe; we provide the systems, training, and auditing that allow the site to be safe.

Key Duty: Keeping the Legal Register current, facilitating risk assessments, and auditing for compliance.

Employees (The Executors):

Responsibility flows both ways. Workers have a legal duty to take care of themselves and others.

Key Duty: Following procedures, using "Stop Work Authority" when unsafe, and reporting near misses.

Auditor’s Insight: The "Organizational Silence" Trap

When roles are unclear, we get "organizational silence." This happens when everyone sees a hazard, but everyone assumes it is someone else's job to report it.

Example: A leaking oil drum is ignored by the forklift driver (thinking "Maintenance will clean it"), ignored by Maintenance (thinking "Cleaning crew handles spills"), and ignored by the Cleaning crew (thinking "That's hazardous waste, Safety handles that").

Result: The oil stays there until someone slips and breaks a leg.

Solution: Clear job descriptions that explicitly state who owns what area and what risk.

4. Training, Awareness, and Competence

This element is the "human firewall" of your safety system. You can have the best policies (Element 1) and the best risk assessments (Element 2), but if the person holding the tool doesn't know how to use it safely, the system fails.

In my years of auditing, I call this the "Paper Shield" problem: companies hide behind thick binders of training certificates while their workers are out on the site making fatal errors. This section of the HSMS is designed to bridge the gap between attending a class and understanding the risk.

Training vs. Competence: The Vital Distinction

The text highlights a massive misconception: that training equals competence. It does not.

Training (The Event): This is the input. It is the classroom session, the PowerPoint presentation, or the online module. It provides knowledge.

Competence (The Outcome): This is the ability to apply that knowledge in a stressful, real-world environment. It requires a combination of three things: Knowledge + Skill + Experience.

Field Example: I can train you on how to drive a forklift in a classroom for 4 hours. But are you competent to drive it carrying a 2-ton load of unstable piping down a wet ramp? No. Competence requires supervision and verified practice.

The Three Components of this Element

To satisfy ISO 45001 or any robust standard, you need to address all three layers:

Training (Technical Skills): This encompasses the formal instruction required to do the job. It ranges from general induction (where are the fire exits?) to high-risk technical training (how to calibrate a gas detector). It must be refreshed regularly—skills fade over time.

Awareness (Psychological Buy-in): Awareness is about the "Why." Workers might know how to wear a harness, but do they understand why it’s critical? Do they understand the consequences of not wearing it—not just the disciplinary action, but the impact on their family? Awareness campaigns focus on human factors and the repercussions of unsafe acts.

Competence (Verified Ability): This is the rigorous validation of skill. In high-risk industries, we use a Competency Matrix to track this. It ensures that a worker doesn't just have a certificate, but has been "signed off" by a supervisor as capable of working alone.

How to Audit "Evidence of Competence"

As an auditor, I view training records with skepticism. A signature on an attendance sheet proves the person was in the room, not that they were listening.

To verify this element, I use the "Show Me" technique:

Don't ask: "Did you receive Lockout/Tagout training?" (They will just say yes).

Do ask: "Show me how you would isolate this specific pump if it started leaking right now."

If the worker fumbles, looks confused, or asks their supervisor for help, they are not competent, regardless of what the paperwork says. An effective HSMS requires practical assessments—drills, observations, and spot checks—to ensure the training actually stuck.

5. Operational Controls

This element is the "Do" phase of the safety cycle. It represents the transition from theoretical planning to physical reality. While Element 2 (Planning) identifies the risk, Operational Controls are the specific barriers you put in place to stop that risk from killing someone.

Here is the operational breakdown of how this functions on site:

The Hierarchy of Controls

This is the golden rule of operational safety. When we define controls, we do not jump straight to PPE. We follow a strict hierarchy to determine the most effective solution.

Elimination (The Best Control) The most effective way to manage risk is to remove it entirely. If you have a noisy generator, the best control is not earplugs; it is replacing the generator with a quiet electric motor. This physically removes the hazard from the workplace.

Engineering Controls (The Hardware) If you cannot eliminate the hazard, you isolate the worker from it. This includes machine guards, ventilation systems for chemical fumes, or interlocks that stop a machine if a door is opened. These are powerful because they work independently of human behavior—they don't rely on a worker remembering to do something.

Administrative Controls (The Rules) These are your procedures: Permit to Work (PTW) systems, Lockout/Tagout (LOTO) protocols, and job rotation schedules to reduce fatigue. These are less effective than engineering controls because they rely on human compliance. A procedure only works if the worker chooses to follow it.

PPE (The Last Resort) Personal Protective Equipment is the least effective control. It does not stop the accident; it only tries to reduce the injury after the accident happens. It should only be used when all other controls are insufficient.

Critical Control Systems

In high-risk environments, operational controls often take the form of rigid systems designed to manage complex hazards.

Permit to Work (PTW) This is a formal authorization system for high-risk tasks like hot work (welding), confined space entry, or working at heights. It forces the supervisor and worker to verbally agree on the hazards and checks before work starts. It is not just a form; it is a handshake agreement on safety.

Lockout/Tagout (LOTO) This is the specific control for hazardous energy. It ensures that machines cannot be turned on while someone is fixing them. It involves physically locking the power source with a padlock that only the maintenance worker has the key to.

Maintenance and Asset Integrity

Operational controls also include the physical upkeep of safety-critical equipment. A fire alarm that hasn't been tested in two years is not a control; it is a wall ornament.

Preventive Maintenance This ensures that the "hardware" of safety works. It includes testing pressure relief valves, inspecting crane cables, calibrating gas detectors, and checking emergency brakes. If the maintenance schedule slips, the operational controls fail.

Contractor Management

Contractors are often the weak link in operational control. They may not know your site, your rules, or your culture.

Bridging Documents Effective control means treating contractors like employees. You must verify their competence, inspect their equipment, and ensure they follow your safety standards, not just their own. If a contractor is unsafe, you are liable.

The Consistency Factor

The true test of operational controls is consistency. It is easy to follow the rules during a Monday morning audit. It is much harder to follow them at 3:00 AM on a rainy Sunday shift when production is behind schedule. A robust HSMS ensures that controls are "habitual"—applied every time, without exception.

6. Monitoring and Measurement

This section acts as the dashboard of your Health & Safety Management System. Just as you wouldn't drive a car without a speedometer or fuel gauge, you cannot run a safety system without data. This element is about gathering the hard evidence to prove whether your controls (Element 5) are actually working or if you are just lucky.

Here is the breakdown of how we measure safety performance in the real world:

The Two Types of Metrics

The most common mistake I see in boardrooms is an obsession with injury rates. While important, injury rates only tell you about the past. A mature HSMS balances two types of data:

Lagging Indicators (The Rearview Mirror) These are retrospective metrics like Lost Time Injuries (LTIs), Medical Treatment Cases, or Worker's Compensation costs. They tell you what went wrong, but they are too late to prevent the accident. Relying only on these is like driving a car while looking only at the road behind you.

Leading Indicators (The Windshield) These are predictive metrics that measure positive safety activities. Examples include the percentage of safety audits completed on time, the number of hazard observations submitted, or attendance rates at safety training. If your leading indicators are trending down (e.g., fewer inspections are happening), it is a warning sign that an accident is coming.

Industrial Hygiene and Technical Monitoring

Monitoring isn't just about checklists; it often requires scientific verification. If you have identified a hazard (Element 2) and installed a control (Element 5), you must use Element 6 to prove it works.

Quantitative Exposure Assessment If you install a ventilation fan to remove welding fumes, you cannot just assume the air is safe. You must use air sampling pumps to measure the concentration of particulate matter. Similarly for noise, you use dosimeters to map the decibel levels in a workshop. This provides legal proof that your workers are not being overexposed.

Equipment Calibration Safety-critical equipment like gas detectors, pressure gauges, and crane load cells drift over time. This element requires a rigid schedule of calibration and testing. If a Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) detector hasn't been bump-tested, it is just a piece of plastic, not a safety device.

The Near Miss Paradox

The text highlights a crucial cultural indicator: the volume of Near Miss reporting.

Why "Zero" is Dangerous If I audit a site with 500 workers and the manager proudly tells me they had "Zero Near Misses" last year, I immediately know the culture is toxic. Statistically, it is impossible for 500 people to work for a year without a single mistake. "Zero reports" usually means workers are afraid of being blamed or they simply don't care enough to fill out the form.

The "Iceberg" Theory We want a high volume of near-miss reports. This data gives us free lessons. Every near miss is an accident that almost happened. By analyzing these "free warnings," we can fix the root cause before someone actually gets hurt. In a healthy HSMS, a spike in near-miss reporting is often celebrated as an improvement in engagement, not a failure of safety.

7. Continuous Improvement

This final element is what separates a "safety manual" from a true management system. In the ISO 45001 framework, this is the "Act" phase. It is the recognition that no safety system is ever "finished." The moment you stop improving your safety protocols is the moment you start drifting toward your next accident.

Here is how Continuous Improvement functions as the engine of long-term safety:

The Cycle of Evolution: The workplace is not static. You buy new machines, regulations change, and experienced staff retire while new apprentices join. If your HSMS stays the same while your business changes, gaps open up. Continuous improvement is the formal process of closing those gaps. It ensures that the system evolves faster than the risks do. It prevents the dangerous mindset of "we’ve always done it this way," which is often the precursor to a major failure.

Learning from Failure (Root Cause Analysis): When an incident or near-miss occurs, a weak system blames the worker ("he didn't look"). A continuously improving system asks why he didn't look. Was he tired? Was the lighting poor? Was the training inadequate? This element requires you to dig deep using tools like Root Cause Analysis (RCA). The goal is to fix the systemic flaw so that no other worker can make that same mistake again. You don't just patch the hole; you reinforce the entire hull.

Audit Findings as Opportunities: Audits (from Element 6) produce "Non-Conformances" (NCs). In a bad culture, managers hide NCs to look good. In a continuous improvement culture, NCs are treated as gold. They are free warnings. Every non-conformance you find and fix is a potential accident you have just prevented. This element tracks those findings to closure, ensuring that corrective actions are actually implemented and not just promised.

The Management Review: This is the strategic steering mechanism. Once a year (or more), Top Management must sit down to review the entire HSMS. This isn't just a safety meeting; it's a business review. They look at the data—accident trends, audit results, worker complaints, and legal changes. They must answer the hard questions: "Is our policy still relevant?" "Do we need to buy better equipment?" "Do we need to hire more safety staff?" This is where the checkbook comes out to support the next level of safety maturity.

The Upward Spiral: Think of continuous improvement as a spiral, not a circle. Every time you go through the PDCA cycle—planning, doing, checking, and acting—you should end up at a higher level of safety than where you started. Year 1 might be about getting everyone to wear hard hats. Year 2 is about reducing noise levels. Year 3 is about behavioral-based safety. The goal is that your site is safer today than it was yesterday, and will be safer tomorrow than it is today.

Conclusion

A Health & Safety Management System is not a static set of binders to be dusted off once a year for an ISO auditor. It is the operational backbone that dictates how your organization survives and thrives in a hazardous world. I have seen firsthand that the companies who treat these seven elements as core business values—rather than regulatory hurdles—are the ones that achieve operational excellence and sustainable growth.

If you are building or revamping your HSMS, start with leadership commitment. No amount of training or protective equipment can compensate for a management team that turns a blind eye to risk. Build a system that empowers your workers, holds leadership accountable, and relentlessly seeks to improve, because ultimately, the success of an HSMS is measured in lives saved and families kept whole.

Comments

Loading...