I was conducting a risk assessment workshop for a turn-around team at a petrochemical plant when a senior supervisor confidently pointed to a drum of benzene and said, "That chemical is a high risk." I had to stop the session right there. The drum, sitting sealed and secured in a bunded area, was certainly a hazard, but in its current state, the risk was actually negligible. It is a distinction I have seen misunderstood on construction sites, in manufacturing floors, and even in corporate boardrooms for over a decade. When professionals conflate these two terms, they prioritize the wrong issues, waste resources on low-value controls, and leave their teams exposed to actual, unmitigated dangers.

This confusion is more than just semantics; it is a fundamental breakdown in safety logic that undermines the entire ISO 45001 framework. In this article, I will strip away the academic jargon and explain the practical, field-based difference between hazard and risk. We will look at how to correctly identify a hazard, how to calculate the actual risk associated with it, and why getting this distinction right is the first step in preventing serious injuries and fatalities.

Defining the Hazard: The Potential for Harm

A hazard is anything with the inherent potential to cause harm, injury, ill health, or damage to property and the environment. In my experience as a Lead Auditor and Risk Management Specialist, the biggest mistake teams make is ignoring dormant hazards. They only look for things actively moving or leaking, rather than analyzing the inherent nature of the environment and materials.

Categories of Hazards

When I walk a site, I categorize hazards mentally to ensure nothing is missed. This structured approach is vital during a Job Safety Analysis (JHA):

Physical: Working at height, suspended loads, high noise levels, electricity, moving machinery parts.

Chemical: Asbestos, silica dust, benzene, welding fumes, cleaning solvents.

Biological: Legionella in water systems, blood-borne pathogens, insect bites in remote field operations.

Ergonomic: Repetitive motion, poor workstation design, heavy manual handling.

Psychosocial: excessive workload, bullying, fatigue, stress.

Note: A hazard exists regardless of whether anyone is interacting with it. A tiger in a cage is a hazard. A 400kV busbar is a hazard, even if the substation is locked.

Defining Risk: The Probability of the Event

Risk is the likelihood that a hazard will cause harm, combined with the severity of that harm. It is a calculation, not an object. When I review risk registers that list "Electricity" as a risk, I send them back. Electricity is the hazard; the risk is the probability of electrocution or arc flash occurring during a specific task.

The Risk Formula

In the field, we generally apply a standard quantitative matrix to determine the risk level:

Risk = Likelihood X Severity

Likelihood: How probable is it that the incident will occur? (e.g., Rare, Possible, Certain).

Severity: If it does happen, how bad will the outcome be? (e.g., First Aid, Lost Time Injury, Fatality).

If I am observing a welder working on a verified isolated line with proper PPE, the hazard (welding fumes/heat) remains, but the risk is Low. If that same welder removes their mask and works in a confined space without ventilation, the hazard is identical, but the risk skyrockets to Critical.

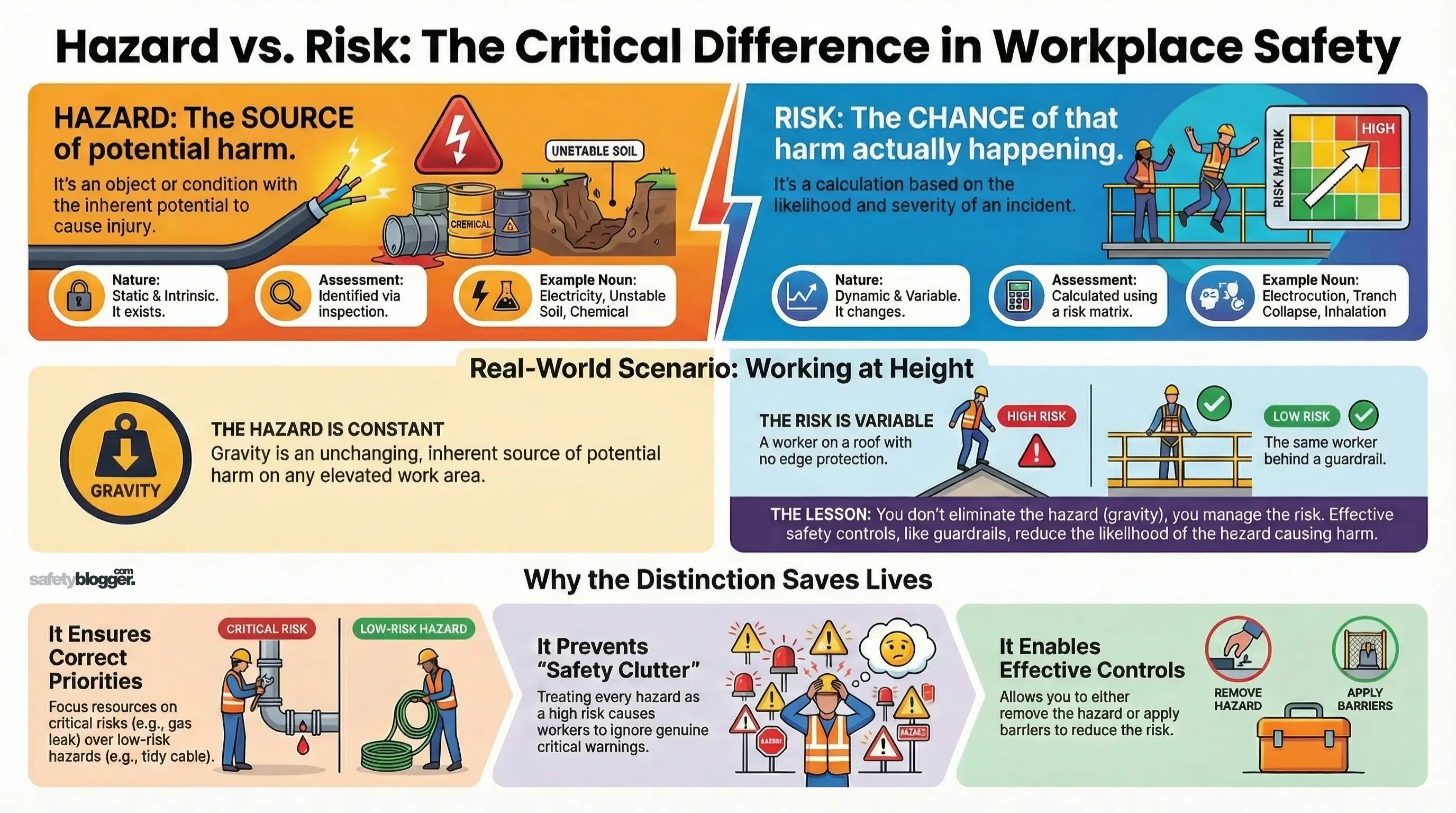

The Practical Comparison: Hazard vs. Risk

I once stopped a lifting operation on a megaproject because the rigging supervisor marked "Crane Failure" as a hazard on the Permit to Work. I had to pull him aside and explain: the crane failing is an event (a risk realization), not the hazard. The hazard is the suspended load and the mechanical tension. If we don't get this distinction right, we implement controls for the wrong things. We prepare for the crash instead of preventing the mechanical stress that causes it.

In my role as a Risk Management Specialist and Lead Auditor, I have found that the most effective way to separate these two concepts is to view them through the lens of Cause vs. Probability.

The Static vs. Dynamic Distinction

The most practical way to differentiate them is to look at their state of being.

Hazard (The Static Enemy): A hazard is an intrinsic property.1 It exists simply because the object or environment exists. A 1000-liter tank of Diesel has the intrinsic property of flammability. That does not change whether the tank is full, half-full, or sitting in a desert. The hazard is "locked in" to the material or situation.

Risk (The Dynamic Variable): Risk is a "living" calculation that changes based on our actions. It is the likelihood of that flammability resulting in a fire, multiplied by the consequence. If I move that diesel tank next to a welding station, the hazard (flammability) hasn't changed, but the Risk has spiked from Low to Critical.

Field Insight: When I audit risk registers, I look for verbs. Hazards usually don't have verbs (e.g., "Electricity," "Silica Dust"). Risks usually have verbs describing an event (e.g., "Electrocution," "Inhaling Dust").

The Comparative Matrix

To visualize this for site teams during toolbox talks, I break down the characteristics directly. This removes the ambiguity.

Feature | Hazard | Risk |

Fundamental Nature | Source. It is the root of the potential damage. | Chance. It is the probability of the damage occurring. |

Can it be eliminated? | Yes. You can remove the source (e.g., use a battery tool instead of a wired one). | Yes. But only by eliminating the hazard. Otherwise, it can only be reduced. |

Does it change? | No. As long as the object exists, the hazard exists. | Yes. It fluctuates constantly based on barriers, distance, and time. |

Assessment Tool | Observation / Inspection / JHA. | Risk Matrix ($L \times S$) / Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA). |

Real-World Scenario Breakdown

To truly master this comparison, we must look at how risk shifts while the hazard remains constant. I use these three scenarios to train Safety Officers on site:

1. Working at Height (The Gravity Hazard)

The Hazard: Gravity. It is constant. It does not care if you are a novice or an expert.

Scenario A: A worker is on a roof with no edge protection.

Risk: High (High likelihood of falling).

Scenario B: The same worker is on the same roof, but behind a certified guardrail.

Risk: Low.

The Lesson: We did not remove the hazard (gravity is still there); we managed the risk by lowering the likelihood of the event.

2. High Voltage (The Energy Hazard)

The Hazard: Electrical Energy (415V).

Scenario A: An electrician opens a panel on a live busbar with no PPE.

Risk: Critical (Arc flash or shock is probable and fatal).

Scenario B: The panel is locked out, tagged out (LOTO), and tested dead.

Risk: Negligible.

The Lesson: The infrastructure (hazard) remains, but the procedural control (LOTO) brought the risk to near zero.

3. Excavation (The Geotechnical Hazard)

The Hazard: Unstable Soil / Weight of Earth.

Scenario A: A 3-meter deep trench with vertical walls and no shoring.

Risk: High (Collapse is likely due to soil physics).

Scenario B: The same trench with trench boxes and stepped battering.

Risk: Low.

The Lesson: The soil type didn't change, but the engineering control altered the risk profile.

Why This Comparison Saves Lives

If you focus only on the hazard, you become paralyzed—everything looks dangerous. A construction site is full of hazards: steel, concrete, heavy iron, fuel.2 If you tried to eliminate every hazard, you couldn't build anything.

By focusing on the risk aspect of the comparison, you become a problem solver. You accept that the hazard is present (e.g., "We must lift this 50-ton beam"), and you focus your energy on the variables you can control: the rigging, the weather window, the exclusion zone, and the competency of the crane operator.

Why the Distinction Matters in Operations

I recall auditing a chemical plant where the safety committee was celebrating a "Zero Harm" milestone. Yet, when I reviewed their corrective action log, I saw they had spent $50,000 upgrading handrails on a rarely used platform (a low-risk hazard) while ignoring a vibrating compressor that was leaking hydrocarbon vapor near a hot surface (a critical risk). They had confused the presence of a hazard (the platform height) with the urgency of a risk (the gas leak).

In my experience as an HSE Manager and Auditor, the distinction between hazard and risk isn't just vocabulary—it is the operating system for decision-making. When Operations teams get this wrong, three critical failures occur: Resource Misalignment, Safety Clutter, and Failure of Controls.

1. The Trap of Resource Misalignment

In every project I have managed, from mining to high-rise construction, resources are finite. We have limited budget, limited manpower, and limited downtime.

If a site manager cannot distinguish between a hazard and a risk, they will treat every hazard as an emergency.

The Error: They see a cable on the floor (Hazard) and a suspended load (Hazard) and treat them with equal weight.

The Consequence: The team spends hours "tidying up" cables (Housekeeping) while a 20-ton load is being lifted over the walkway without a proper lift plan.

The Reality: We must prioritize. We live with hazards constantly. We cannot live with high risks. Understanding the difference allows a manager to say, "The cable is a hazard, but the risk is low. The lift is a hazard, and the risk is critical. Focus on the lift."

2. "Safety Clutter" and Worker Desensitization

When we label everything as a "High Risk," workers stop listening. I call this "Safety Clutter."

I once walked a site where the "Risk Assessment" listed "Paper Cuts" next to "Amputation." By elevating a minor hazard to the level of a catastrophic risk, the safety department lost all credibility. The workers reasoned, "If they think paper cuts are a major issue, they clearly don't understand my job."

Hazard Awareness: Recognizes that the danger exists (e.g., "This chemical is toxic").

Risk Perception: Tells the worker how to behave (e.g., "I must wear a respirator because the likelihood of inhalation is high").

If we blur the lines, we create a "Cry Wolf" culture where genuine warnings about high-voltage or confined spaces are ignored because they are buried in a sea of trivial warnings.

3. The Hierarchy of Controls Breakdown

This is the most technical and dangerous failure. The Hierarchy of Controls—the global standard for safety systems—relies entirely on this distinction.

Top Levels (Elimination/Substitution): These attack the Hazard. You are removing the source of the harm.

Example: Replacing a solvent-based paint with a water-based one. The hazard (toxicity) is gone.

Bottom Levels (Engineering/Admin/PPE): These attack the Risk. The hazard is still there, but you are placing a barrier to reduce the likelihood of contact.

Example: Installing a machine guard. The spinning blade (hazard) is still spinning, but the risk (likelihood of contact) is reduced.

The Operational Failure: When teams confuse the two, they often try to solve a Hazard problem with a Risk solution.

Scenario: A noisy generator causes hearing loss (Hazard).

Wrong Approach: "Let's put up a sign saying 'Caution: Noise'" (Admin Control). This addresses the risk poorly but leaves the hazard raging.

Right Approach: "Let's enclose the generator or buy a quieter one" (Engineering/Elimination). This attacks the hazard directly.

Field Insight: If you find yourself constantly adding more PPE or more signs, you are fighting the risk while letting the hazard survive. True safety improvement usually comes from attacking the hazard itself.

Conclusion

Understanding the difference between hazard and risk is not just an academic exercise for safety managers; it is the foundation of a safe workplace. A hazard is the potential for harm that sits in your blind spot; risk is the calculation of how likely it is to strike. If your team cannot distinguish between the two, they cannot prioritize their defenses, leaving them vulnerable to the dangers that truly matter.

We must move beyond tick-box safety where everything is labeled "dangerous." True safety leadership involves accurately identifying hazards, honestly assessing the risks, and implementing robust controls that work in the real world. At the end of the day, our goal is not to produce perfect paperwork, but to ensure that the risk level is low enough for every father, mother, son, and daughter to go home safe

Comments

Loading...