I once sat across from a Project Manager who was trembling after a subcontractor fell from an uncertified scaffold on his site. He kept repeating, "But I hired a safety officer, isn't that enough?" It was a difficult moment, but I had to explain that hiring safety staff does not absolve leadership of their fundamental obligation. He had assumed safety was a department; he failed to realize that Duty of Care is a non-delegable legal and ethical backbone that dictates every decision we make, from budget approvals to shift scheduling.

In my decade of auditing high-risk sites—from petrochemical plants to urban infrastructure—I have seen that "Duty of Care" is often the most misunderstood concept in HSE. In this article, I will break down exactly what this term means, moving beyond the legal textbooks to the reality of the field. We will define the obligations of both the employer and the employee, explain the critical test of "reasonable practicability," and outline the severe consequences when this duty is ignored.

Defining Duty of Care in the Workplace

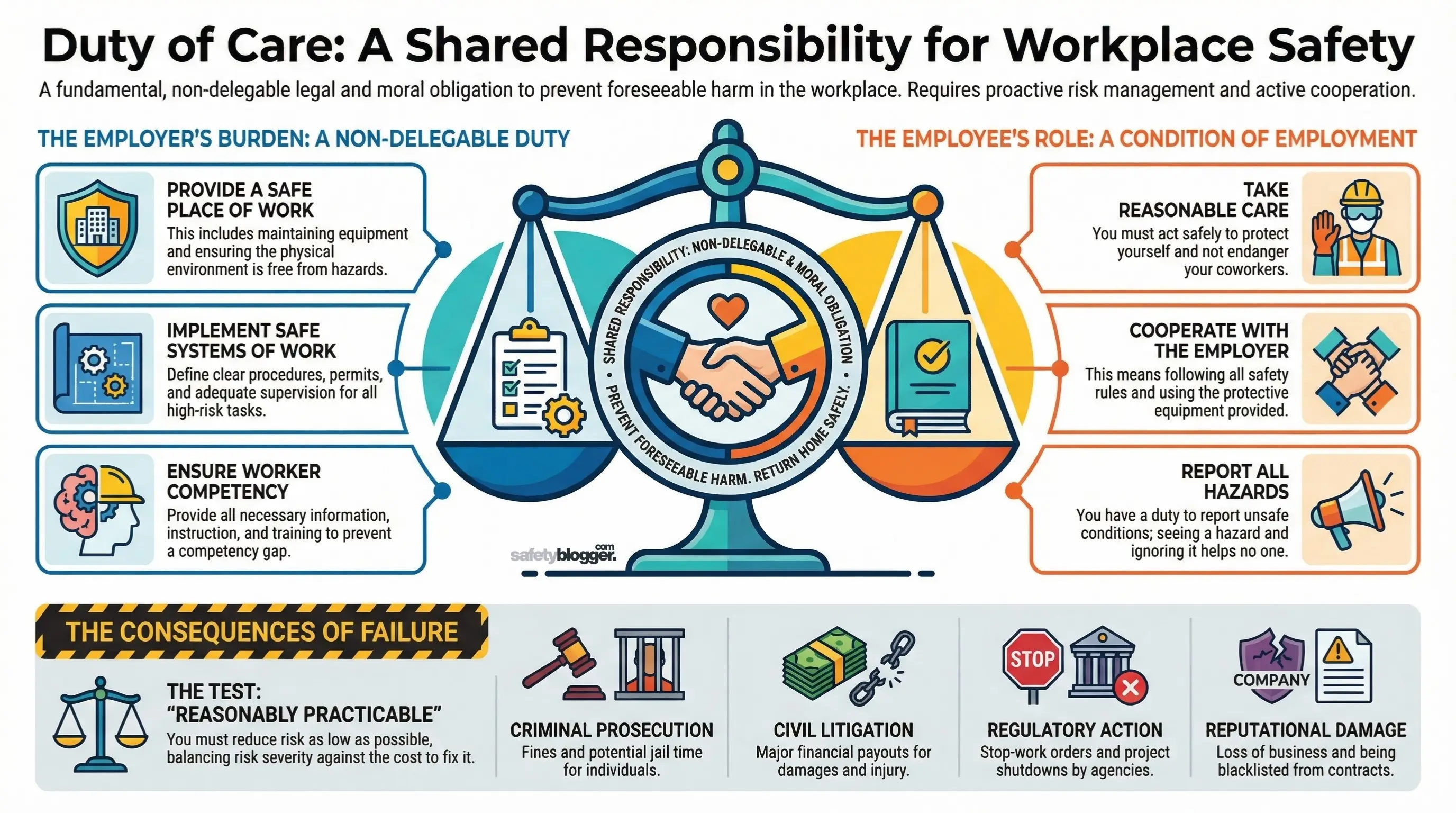

At its core, Duty of Care is the legal and moral obligation to ensure that others are not harmed by your activities, omissions, or decisions. It is not optional, and it cannot be transferred to someone else. In simple terms, if you create a risk, you own the responsibility for managing it.

For an organization, this means you must anticipate "foreseeable" risks. If you are running a quarry, you know that silica dust is a hazard. If you fail to install suppression systems because "nobody complained yet," you are breaching your duty of care. It is about taking proactive steps to prevent harm, ensuring that workers return home in the same condition they arrived.

Key Principle: Ignorance is never a defense. You cannot say "I didn't know that chemical was toxic" if it is a recognized hazard in the industry.

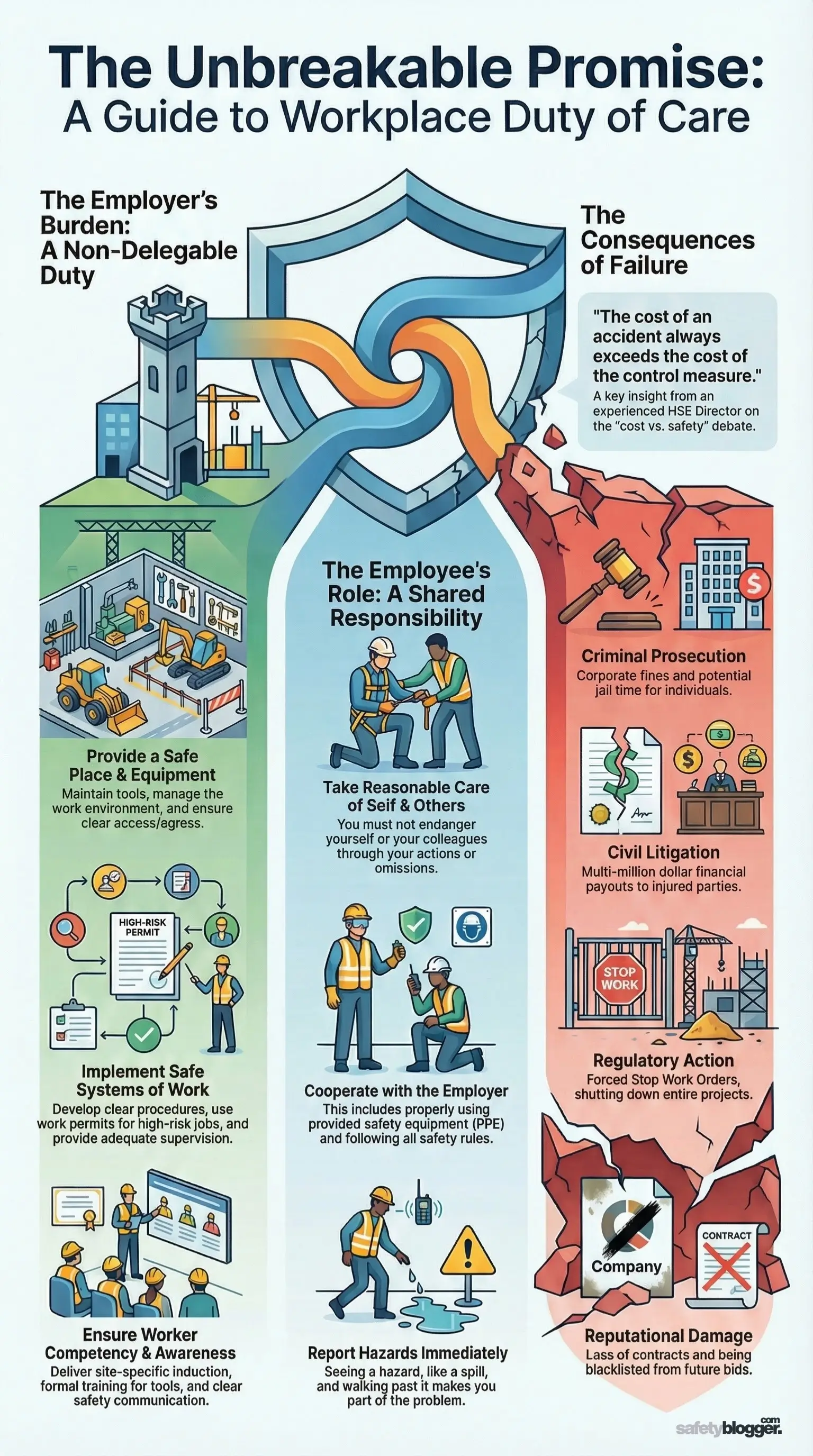

The Employer’s Burden: A Non-Delegable Duty

The heaviest weight of this duty falls on the employer. In my role as an HSE Director, I constantly remind Boards that they provide the "platform" for work. If that platform is unstable—physically or culturally—they are liable.

Safe Place of Work and Equipment

The employer must provide a physical environment that does not pose unreasonable risks. I have audited factories where guards were removed from rotating machinery to "speed up production." That is a direct breach. The duty requires:

Maintenance: Ensuring cranes, forklifts, and tools are serviced and safe.

Environment: Managing lighting, ventilation, noise, and temperature.

Access/Egress: Keeping walkways clear and emergency exits unlocked.

Safe Systems of Work (SSOW)

Hardware is useless without a plan. You must have a defined method for doing dangerous work.

Permit to Work: For high-risk tasks like confined space entry or hot work.

SOPs: Written procedures that reflect how the job is actually done, not just how it looks on paper.

Supervision: You cannot throw a rookie into a complex task alone. The level of supervision must match the level of risk and the worker’s experience.

Information, Instruction, Training, and Supervision

One of the most common failures I investigate is the "competency gap." Placing an untrained worker in a hazardous role is negligence.

Induction: Every worker must know the specific hazards of this site.

Training: Formal certification for specific tools (e.g., abrasive wheels, excavators).

Communication: Safety alerts and updates must reach the shop floor, not just stay in email inboxes.

The Employee’s Role: It Takes Two

While employers hold the primary duty, employees are not passengers. I often tell union reps and work crews that safety is a condition of employment. Under most legislation (like the UK’s Health & Safety at Work Act or OSHA standards), employees have their own statutory duties.

Reasonable Care for Self and Others

You must take care of your own safety and that of your coworkers. If I see a rigger standing under a suspended load, he is breaching his duty of care to himself. If a forklift driver speeds around a blind corner, he is breaching his duty to pedestrians.

Duty to Cooperate

Employees must work with the employer to meet safety goals.

PPE: If the company provides hard hats and you refuse to wear one, you are liable.

Following Rules: Intentionally bypassing safety interlocks or ignoring permits is a violation of your duty.

Reporting: You have a duty to report hazards. Seeing a spill and walking past it makes you part of the problem.

The Litmus Test: "Reasonably Practicable"

This is the concept that causes the most confusion in boardrooms. We are not required to eliminate all risk—that is impossible in industries like mining or construction. We are required to reduce risk "As Low As Reasonably Practicable" (ALARP).

This involves a balancing act:

The Risk: How likely is the accident, and how bad would it be (Severity)?

The Sacrifice: What is the cost (time, money, effort) to prevent it?

If the risk is a fatality, the "cost" argument is almost never valid. However, if the risk is a bruised knee and the solution costs $5 million, that might be considered disproportionate.

Pro Tip:

If you are debating "cost vs. safety," you are usually on the wrong side of the argument. In my experience, the cost of an accident—investigation, legal fees, downtime, morale drop—always exceeds the cost of the control measure.

The Consequences of Failure

What happens when Duty of Care is breached? It is not just a slap on the wrist. I have seen companies fold and careers end because they failed this fundamental test.

Consequence Category | Impact | Real-World Example |

Criminal Prosecution | Fines and Jail Time. | A site manager imprisoned for Gross Negligence Manslaughter after a trench collapse. |

Civil Litigation | Financial Payouts. | A company sued for millions by an employee who developed chronic back pain due to poor ergonomics. |

Regulatory Action | Stop Work Orders. | A regulatory body (like OSHA or HSE) shutting down an entire project until compliance is proven. |

Reputation | Loss of Business. | Being blacklisted from bidding on government or major corporate contracts due to a poor safety record. |

Conclusion

Duty of Care is the thread that holds the entire safety management system together. It moves safety from a checklist exercise to a human imperative. It means that when we walk onto a site, we are making a silent promise to look out for one another—from the Director's office to the excavation pit.

In my professional opinion, the organizations that truly understand this don't just have lower accident rates; they have higher morale, better quality, and higher productivity. Safety is not separate from the work; it is the way we do the work. Fulfilling your duty of care is the ultimate sign of professional competence.

Comments

Loading...