I was recently sitting across the desk from a Site Director during a tense ISO 45001 surveillance audit. We were discussing their confined space entry procedures, which deviated significantly from the standard industry practice. When I pointed out that his method statement contradicted the relevant Approved Code of Practice (ACOP), he shrugged and said, "Badr, that’s just a code of practice. It’s advice, not the law. We don’t have to follow it."

He was technically right, but legally, he was walking into a trap that has destroyed countless companies in court. That dismissal of an ACOP is one of the most dangerous misconceptions in industrial safety. While he believed he was exercising operational flexibility, he was actually reversing the burden of proof onto himself in the event of an accident. If a fatality occurred, he wouldn't just have to prove he wasn't negligent; he would have to prove to a judge that his "alternative method" was equally as effective as the methods written by the HSE. That is a much higher bar to clear than most managers realize.

In this article, I will strip away the legal jargon and explain the critical operational difference between Regulations and Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs). We will look at why treating them as "just advice" is a strategic failure, and how understanding their distinct legal status can protect you from prosecution.

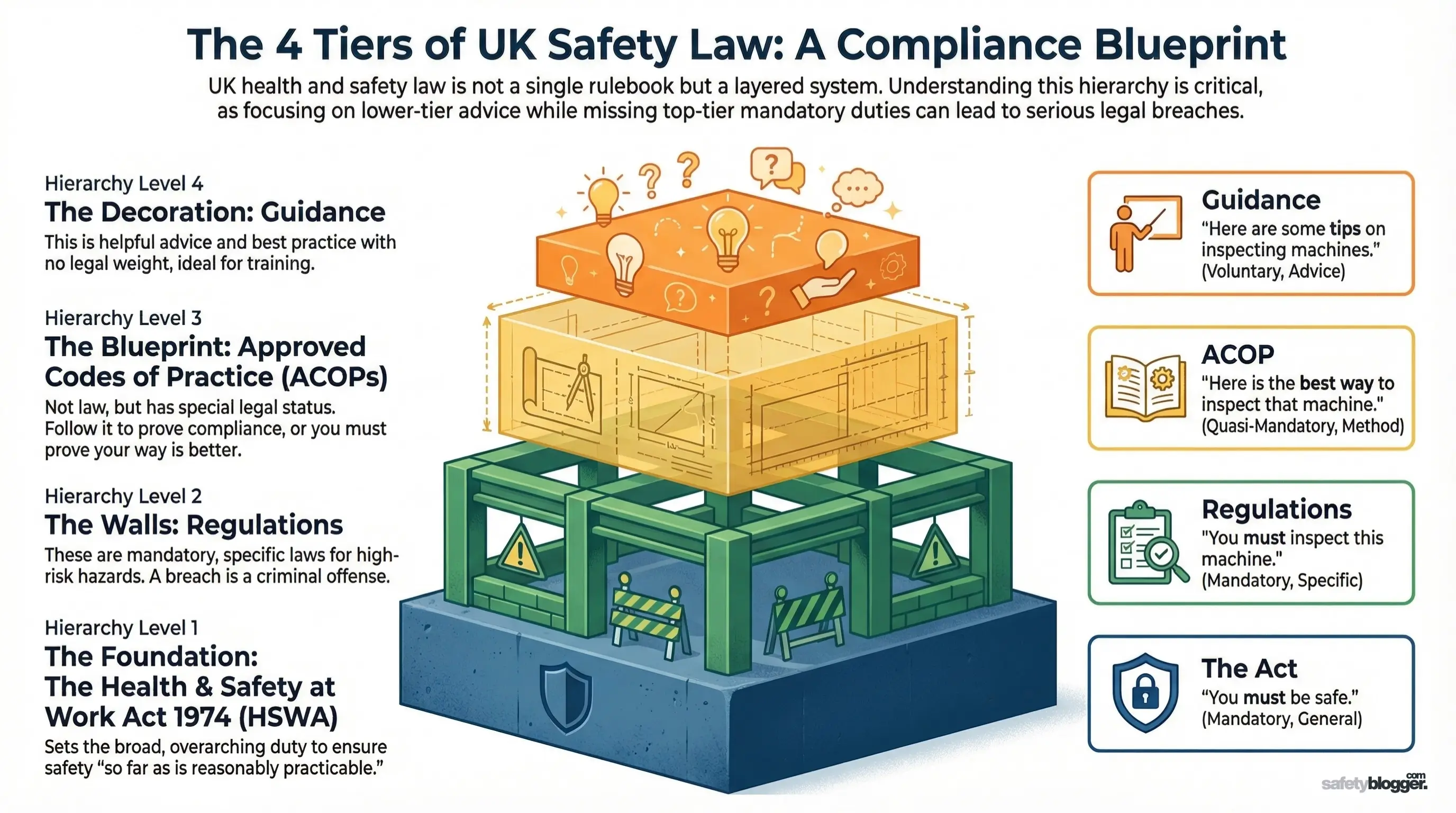

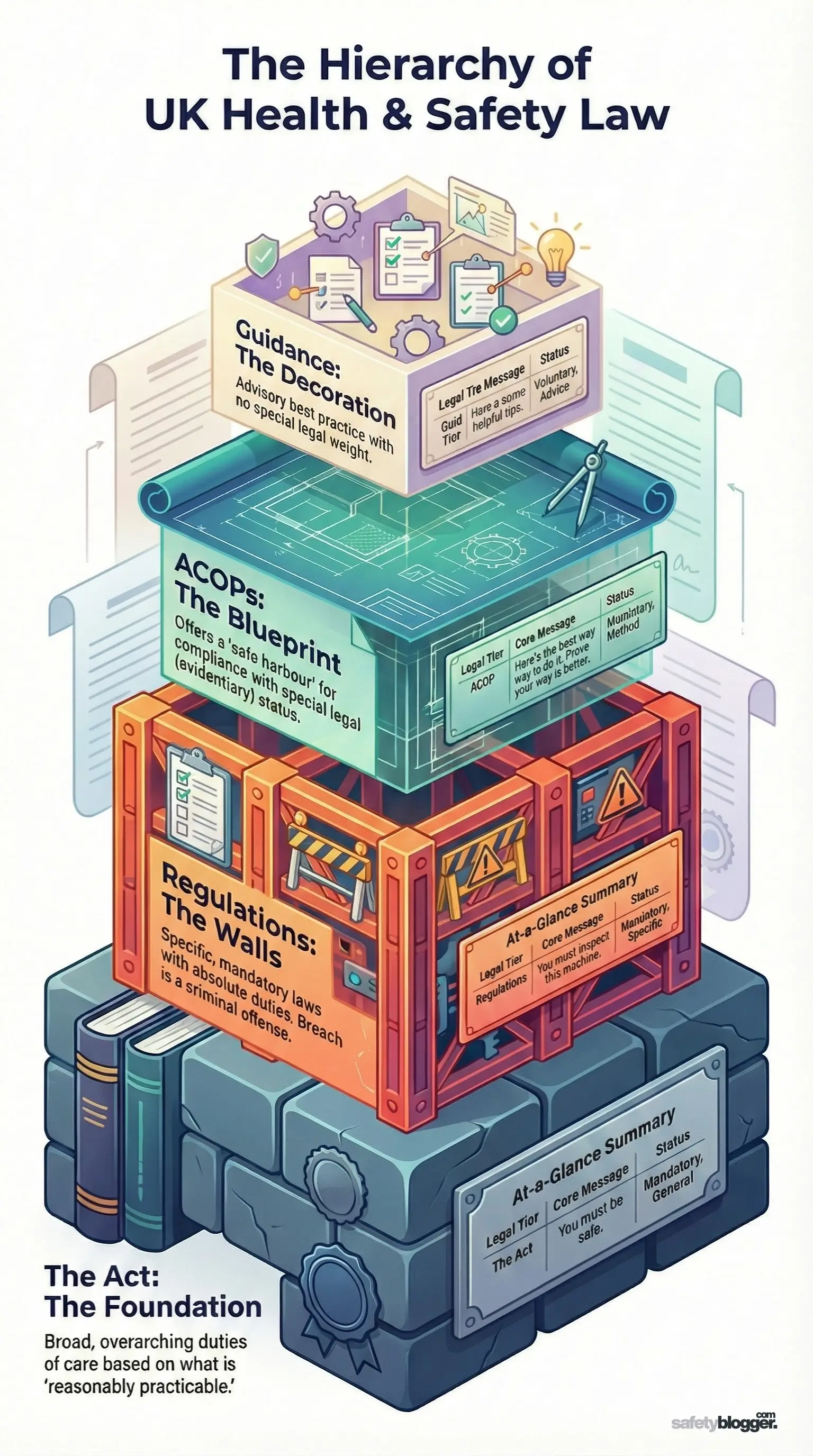

The Hierarchy of Safety Law

This is the single most important concept in UK health and safety law. If you get this hierarchy wrong, you might spend time over-engineering a solution based on "Guidance" while missing a mandatory requirement hidden in a "Regulation."

1. The Foundation: The Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HSWA)

Think of the HSWA as the concrete slab foundation of a building. It doesn't tell you what the rooms look like or where the windows go, but it supports everything else. If you breach this, the whole structure collapses.

The Core Philosophy: The Act is "Enabling Legislation." It doesn't deal with specifics like asbestos or noise. Instead, it sets out the broad, sweeping duties of care.

Key Concept – "Reasonably Practicable": This is the most famous phrase in safety law (Section 2(1)). It requires you to balance the level of risk against the cost/effort of controlling it.

Real World Application: The Act says you must ensure safety "so far as is reasonably practicable." It does not demand zero risk. It demands that you do everything reasonable to prevent harm.

Who it targets: It targets everyone. Employers (Section 2), Self-Employed (Section 3), Controllers of Premises (Section 4), and even Employees (Section 7).

Field Note: You are rarely prosecuted just under the Act unless there was a catastrophic, systemic failure of management (like a total lack of safety culture). Usually, prosecutors attach specific Regulation breaches to the charge.

2. The Walls: Regulations (The Hard Law)

If the Act is the foundation, Regulations are the load-bearing walls. These are Statutory Instruments (law made by Ministers) that give specific orders.

No Wiggle Room: Unlike the Act, which allows for "reasonable practicability," many Regulations create Absolute Duties.

Example: The Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) says "Every employer shall ensure that work equipment is maintained in an efficient state." It doesn't say "if you can afford it" or "if you have time." It says shall.

Specific Hazards: Regulations are written when the government decides a specific hazard (like radiation, chemicals, or heights) is too dangerous to be left to general interpretation.

COSHH (Chemicals)

LOLER (Lifting)

DSEAR (Explosives)

Criminal Offence: A breach of a regulation is a criminal offence. You don't need to hurt anyone to be prosecuted; you just need to break the rule.

Field Note: When I audit, I check Regulations first. "Did you inspect the crane every 6 months as per LOLER?" If the answer is "No," the audit fails immediately. There is no debate.

3. The Blueprint: Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs)

This is the "Special Middle Ground" and the most misunderstood layer. ACOPs explain how to comply with the Regulations.

The "L-Series": You can identify these books because their code starts with 'L' (e.g., L101 Safe Work in Confined Spaces).

Quasi-Legal Status: As mentioned, they are not law, but they have special evidentiary weight under Section 17 of the HSWA.

The "Safe Harbour": Think of an ACOP as a deal with the government. The HSE says: "The law is complicated. If you follow this book (ACOP), we promise to accept that you have followed the law."

The Danger Zone: If you ignore the ACOP, you are sailing into open water without a map. You are permitted to use a different method, but the burden of proof reverses. You must prove your way is safe; the HSE doesn't have to prove it's unsafe.

Field Note: I once saw a Site Manager try to use a "drone inspection" for a confined space instead of the physical entry testing outlined in the ACOP. It was a smart idea, but he hadn't documented why it was equally effective. When we dug into the data, the drone couldn't detect heavy gases at the bottom of the tank. He was unknowingly in breach of the law because his "better way" was actually inferior to the ACOP.

4. The Interior Decoration: Guidance

Finally, we have Guidance. This includes HSE Leaflets (INDG series) and Health and Safety Guidance (HSG series).

Pure Advice: These documents are helpful. They contain good ideas, diagrams, and industry best practices.

Legal Weight: They have no special legal status.

If you don't follow Guidance, you won't automatically be found at fault. However, if an accident happens, a lawyer might still wave the Guidance in court and ask, "Why did you ignore the industry best practice?"

Flexibility: You are free to ignore Guidance if you have a operational reason, provided you still meet the Regulations and ACOP.

Field Note: Guidance is great for training your team ("Here is a leaflet on how to sit correctly"), but never build your corporate compliance strategy solely on Guidance. It is too soft. Build your strategy on Regulations and ACOPs.

Summary Visualization

The Act: "You must be safe." (Mandatory, General)

Regulations: "You must inspect this machine." (Mandatory, Specific)

ACOP: "Here is the best way to inspect that machine. If you do it differently, you better be right." (Quasi-Mandatory, Method)

Guidance: "Here are some tips on inspecting machines." (Voluntary, Advice)

Regulations: The "Must"

When you read a Regulation, you are not reading a guideline; you are reading the instruction manual for staying out of prison. Regulations act as the "load-bearing walls" of the UK legal framework. They identify specific high-risk hazards—asbestos, noise, lifting operations, electricity—and dictate the absolute minimum standard you must achieve.

In my experience as an auditor, a "breach of regulation" is usually binary. There is no gray area for negotiation. You either complied, or you committed a criminal offence.

The Binary Nature of Compliance

Many Regulations impose what we call an Absolute Duty. This means the argument of "cost" or "effort" is irrelevant in court.

Scenario: You failed to report a specified injury (like a fracture) under RIDDOR within the statutory timeframe.

The Defence: You claim the site was busy, the internet was down, or the manager was on leave.

The Verdict: You are guilty. The Regulation demanded an action (reporting), and you failed to deliver it. The judge looks at the outcome, not the intent.

The "What" vs. "How" Problem

However, Regulations create a specific frustration for site managers: they are often short, dry, and purely goal-oriented. They tell you what outcome to achieve, but they rarely tell you how to engineer it.

Take PUWER Regulation 11 (Dangerous Parts of Machinery) as a prime example:

The Command: It simply says you "must prevent access" to dangerous parts.

The Silence: It does not tell you how high the fence must be, what mesh size to use, or how far back from the blade it needs to sit.

This is the dangerous gap in the law. The Regulation demands safety, but gives you no blueprints. If you stop reading here, you are guessing—and in high-risk industries, guessing gets people hurt. This is exactly why the Approved Code of Practice (ACOP) exists.

ACOP: The "Special Legal Status" (The Legal Trap)

This section is the intellectual core of the article. If you understand this, you understand how to protect yourself from prosecution. If you don't, you are gambling with your freedom. Here is the deep-dive explanation of Section 17, the Reverse Burden of Proof, and why the "Legionella" example is the perfect illustration of this legal concept.

1. Section 17: The "Teeth" of the ACOP

Most people assume that because an Approved Code of Practice (ACOP) is not a "Regulation," it is voluntary. That is a dangerous half-truth.

Section 17 of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 is the legal mechanism that gives ACOPs their power. It explicitly states that an ACOP is admissible in evidence in criminal proceedings.

Normal Guidance: If you ignore a generic HSE leaflet, the prosecutor has to argue why that matters.

ACOP: If you ignore an ACOP, the law automatically accepts that you have failed to do what is required, unless you can prove otherwise.

2. The "Reverse Burden of Proof" Explained

In a standard criminal case (like theft), the prosecution must prove you are guilty "beyond reasonable doubt." You (the defendant) generally don't have to prove anything; you just have to poke holes in their story.

In Health & Safety Law regarding ACOPs, this flips.

Here is the courtroom sequence if you ignore an ACOP:

The Prosecution: "Your Honour, the defendant did not follow the method outlined in ACOP L101."

The Court: "Okay, we now assume the defendant is in breach of the Regulation."

The Shift: The burden now shifts to YOU. You must stand up and prove that your alternative way was safe.

Why is this a nightmare? Proving a negative or proving technical equivalence is incredibly difficult and expensive. You need expert witnesses, years of data, and scientific modelling. If your "alternative method" was just a hunch or a cost-saving measure, you have zero defence. You are guilty by default.

3. Deep Dive: The Legionella Example (L8)

I chose the Legionella example because it is scientifically rigid. You cannot argue with biology.

The Science: Legionella bacteria go dormant below 20°C and die above 60°C. The "Danger Zone" is between 20°C and 45°C.

The ACOP (L8) Solution: The ACOP is simple physics: Keep the hot water hot (50°C+ at outlet) and the cold water cold (below 20°C). If you do this, the bacteria cannot survive.

Scenario A: The "Safe Harbour" (Following the ACOP)

Action: You maintain your calorifiers at 60°C and your outlets at 50°C.

The Incident: Despite this, a biologically freak event occurs, and someone contracts Legionnaires' disease.

The Defence: You show the judge your temperature logs. You followed the HSE's own book to the letter.

The Outcome: It is very hard to convict you of negligence when you did exactly what the government told you to do. You are in the "Safe Harbour."

Scenario B: The "Arrogant Deviation" (Ignoring the ACOP)

Action: You think 50°C is too expensive. You lower the water to 42°C (perfect for bacteria growth) but add a Chlorine Dioxide dosing unit.

The Incident: The dosing unit gets an airlock, the chemical stops flowing, and the bacteria explode. Someone dies.

The Prosecution: "You knowingly created a temperature environment where bacteria thrives, violating the ACOP."

The Defence: You have to prove that your chemical dosing unit was 100% as reliable as the physics of heat.

The Reality: Mechanical dosing fails more often than simple thermodynamics. You cannot prove equivalence. You are found guilty of breaching the COSHH Regulations.

Summary for the Field

The lesson here isn't "never deviate." The lesson is "never deviate without proof."

If you are going to ignore an ACOP, you better have a file on your desk containing a risk assessment so robust that it could withstand a cross-examination by a King's Counsel barrister. If you don't have that file, go back to the Code.

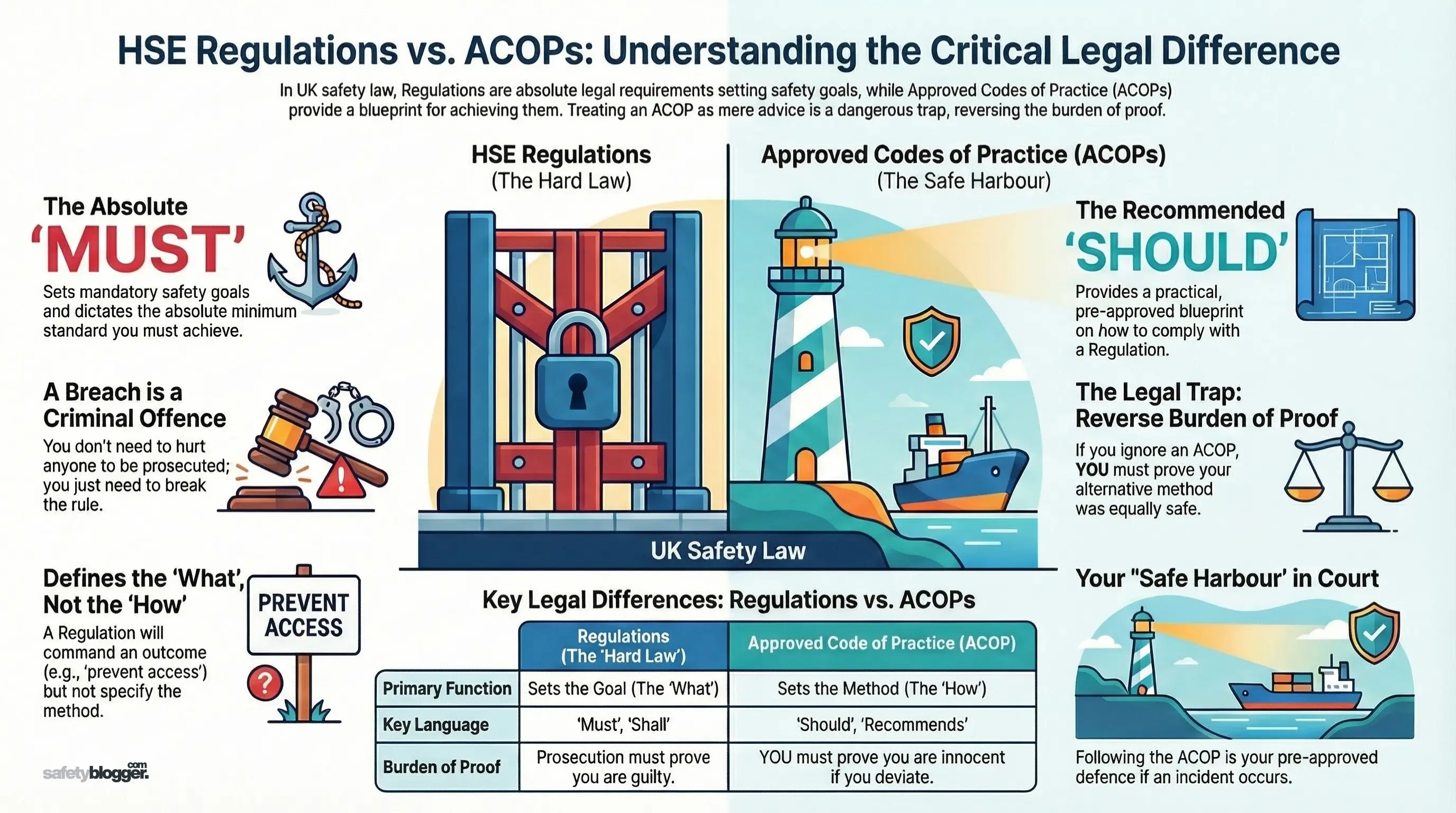

Comparison: Regulations vs. ACOPs

Feature | Regulations (The "Hard Law") | Approved Code of Practice (ACOP) |

Legal Classification | Subordinate Legislation (Statutory Instrument). These are laws made by Ministers under powers granted by the HSWA 1974. | Quasi-Legal Guidance. Approved by the HSE Board with the consent of the Secretary of State. |

Primary Function | Sets the Goal. Defines the absolute duty or outcome (e.g., "Prevent access to dangerous parts"). | Sets the Method. Provides the practical blueprint on how to achieve that goal (e.g., "Use a 2m high fence"). |

Mandatory Status | Absolute / Strict. You have no choice. Non-compliance is automatically a criminal offence. | Conditional. You should follow it, but you may use alternative methods if they are equally effective. |

Key Language (Verbs) | "Must", "Shall".(e.g., "The employer shall ensure...") | "Should", "Recommends".(e.g., "Duty holders should consider...") |

Courtroom Role | The Charge. You are prosecuted for breaching the Regulation itself. | The Evidence. The ACOP is used by the prosecutor to prove you breached the Regulation. |

Burden of Proof | Prosecution's Burden. The prosecutor must prove beyond reasonable doubt that you failed to meet the standard. | Reverse Burden (Defendant's Burden). If you ignore the ACOP, the court assumes you are at fault. YOU must prove your innocence by proving your method worked. |

Flexibility for Innovation | None. You cannot "innovate" your way out of a mandatory reporting duty or a specific exposure limit. | High. Allows for new technology. If a new robot is safer than the ACOP method, you can use it (provided you can prove it). |

Audit Consequence | Automatic Major Non-Conformance. If you breach a regulation, the audit is failed immediately. No debate. | Justification Required. If you deviate, the auditor asks: "Where is the technical assessment proving this is safe?" If missing $\rightarrow$ Major NC. |

Defense Strategy | Factual Denial. "I did not break the rule." (You have to prove the event didn't happen). | Technical Justification. "I broke the rule in the book, but my engineering solution offers a higher protection factor." |

Scientific Validity | Static. Often outdated. Laws take years to change. (Some regulations still reference old tech). | Dynamic. Updated more frequently to reflect current industry best practices and known failures. |

Cost Implication | Non-Negotiable. You must spend the money to comply, regardless of profit margins. | Value Engineering Possible. You can sometimes find a cheaper way to achieve the same safety result, but you own the risk. |

Example (Confined Space) | Confined Spaces Regulations 1997:"No person shall enter a confined space... unless it is not reasonably practicable to achieve that purpose without such entry." | L101 ACOP:"If entry is unavoidable, you should operate a permit-to-work system with specific gas testing intervals." |

Practical Application: When to Deviate?

In safety management, we often talk about "innovation" and "flexibility." But when it comes to Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs), flexibility is a double-edged sword. This section warns you that while you can legally deviate from an ACOP, doing so is often a strategic mistake unless you have the budget and brains to back it up. Here is why I call this the "Competency Trap" and exactly what I look for when I audit these decisions.

1. The "Competency Trap"

I coined this term after investigating a serious incident at a manufacturing plant. The Engineering Manager decided to ignore the ACOP for machine guarding (which recommended fixed guards) and instead installed a complex system of light sensors (a deviation).

The Trap: He was smart enough to install the sensors, but he wasn't smart enough to calculate the "stop-time" (how fast the machine stops after the beam is broken). The machine had too much momentum. A worker reached through the light curtain, and the machine was still spinning when his hand touched the blade.

The Lesson:

Following the ACOP (Fixed Guard): You just need to know how to use a tape measure. It’s simple.

Deviating (Light Curtain): You need to understand physics, momentum, circuit response times, and safety integrity levels (SIL).

Why it matters: If you deviate, you are claiming you know better than the HSE experts who wrote the code. That is a bold claim. If you are wrong, you are negligent.

2. The Cost of Deviation

Most managers deviate to save money (e.g., "That ACOP scaffolding is too expensive, let's use ladders").

This is false economy. To deviate legally, you must spend more money on engineering verification than you would have spent just following the rules.

To follow the rules: Buy the standard equipment.

To break the rules: Hire a consultant, run a trial, document the data, and get legal sign-off.

If you are deviating to save money, you are almost certainly breaking the law.

3. The "Justification File" (The Auditor's Weapon)

When I walk onto a site as an auditor, I am looking for the "Golden Thread" of evidence. If I see you performing a high-risk task (like Confined Space Entry) in a way that looks different from the ACOP (L101), I stop and ask for the Justification File.

This is not a mental note. It must be a physical or digital folder containing three specific things:

A. The Comparative Risk Assessment

A standard risk assessment is not enough. You need a Comparative Risk Assessment.

Standard: "Is this safe?"

Comparative: "Is this safe compared to the ACOP method?"

The Question: You must explicitly write: "We considered the ACOP method (X), but we rejected it because of (Y). We have chosen method (Z) because it offers superior protection against hazard (A)."

B. Proof of Equivalence (The Data)

You cannot just say it's safe. You must prove it.

Example: If the ACOP says "test air every 15 minutes," and you want to test "every hour," where is the data showing that gas levels on your specific site never fluctuate faster than 60 minutes?

No Data? Then you are guessing. And guessing is a Major Non-Conformance.

C. Competent Sign-Off

Who made the decision?

If the "Site Supervisor" signed off on a deviation from a major safety code, I will fail the audit. They do not have the legal authority or technical depth.

I expect to see the signature of a Technical Authority—a Process Safety Engineer, a Certified Hygienist, or the HSE Director. This shows the company takes the deviation seriously.

Summary for the Field

When you are tempted to say, "Let's just do it this way, it's faster," stop. Ask yourself:

"Am I willing to stand in court, look a judge in the eye, and explain the physics of why my idea is better than the government's official code?"

Conclusion

The distinction between Regulations and ACOPs is not just semantics for lawyers; it is the difference between a secure defense and a legal disaster.

Regulations are your obligations. They set the goalposts.

ACOPs are your safe harbour. They are the HSE saying, "If you do it this way, we won't prosecute you for the method."

As a safety professional, you should treat ACOPs as the default operating standard. Only deviate if you have a compelling technical reason and the evidence to back it up. In the eyes of the law, arrogance is not a defense, and "we've always done it this way" will not save you from a judge who holds the ACOP in one hand and your accident report in the other.

Next Step: Review your high-risk activities (Confined Space, Legionella, Lifting). Are your procedures based on the relevant L-Series ACOP? If you have deviated, do you have the documented proof that your method is equally safe? If not, bring it back to the Code.

Comments

Loading...