I once sat in a post-incident review for a dropped object incident where a 5kg scaffolding clamp missed a worker’s head by inches. The project manager was baffled: "But Badr, their safety manual is 400 pages long, and they are ISO 45001 certified!" I opened the manual to page 30—it still referenced "British Rail," even though we were building a refinery in the Middle East. It was a copy-paste job. That contractor had great paperwork but zero operational discipline. They were a "paper tiger," and they almost killed someone on my watch because we didn't dig deep enough during the selection phase.

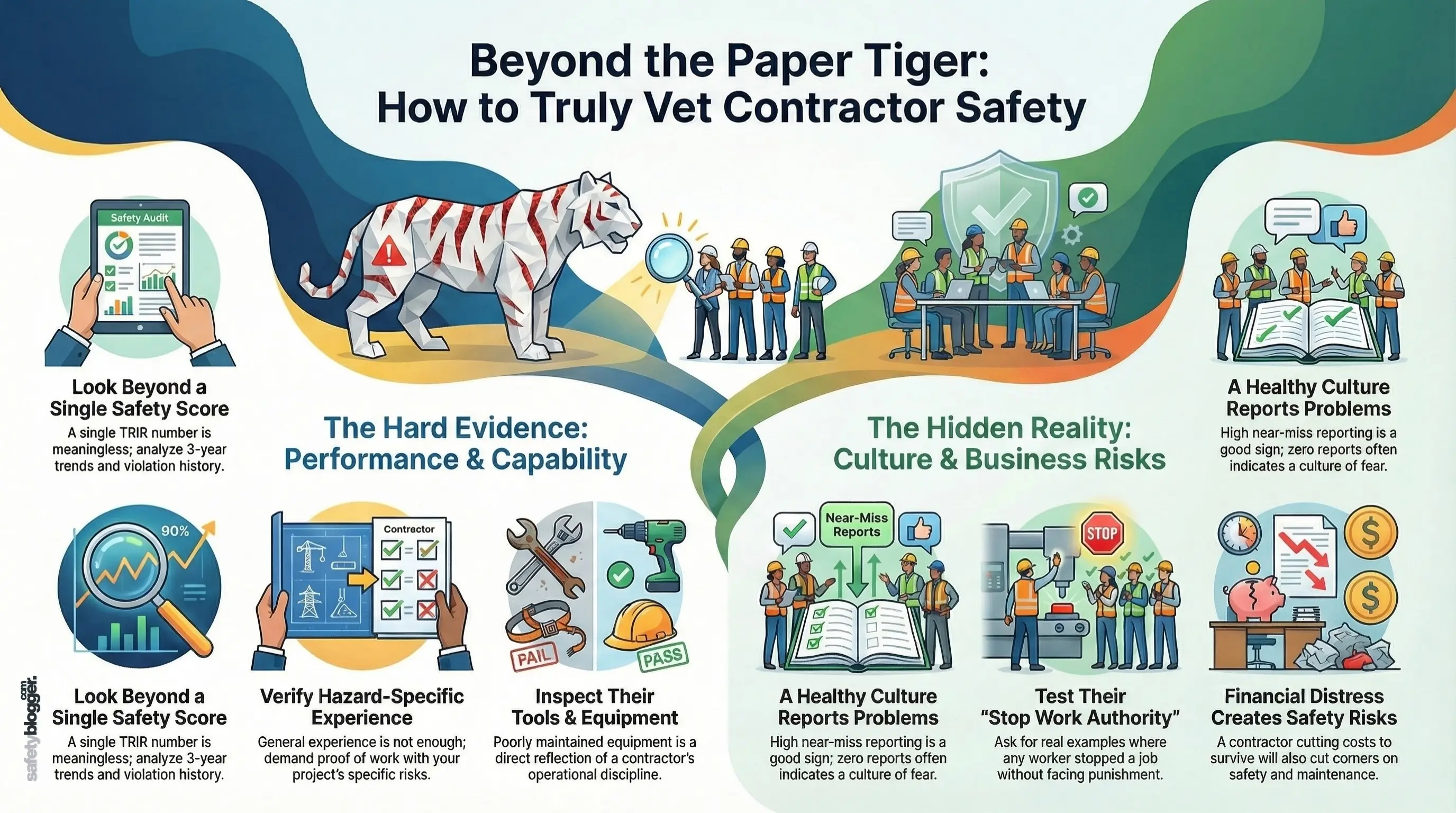

Hiring a contractor is the single biggest transfer of risk a company undertakes. When you bring an external workforce onto your site, you inherit their culture, their shortcuts, and their hidden incompetence. A generic "Pass/Fail" checklist is not enough to protect your business or your people. You need to interrogate their systems, audit their field reality, and look past the polished sales pitch. Based on my experience auditing contractors from mining camps to offshore platforms, here are the 15 critical factors you must evaluate, explained in detail.

The Lagging Indicators (Historical Performance)

These numbers are your first filter. They tell you what has happened in the past, but be warned: in the HSE world, past performance is not always a guarantee of future safety—especially if the data is manipulated.

1. Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR) Trends

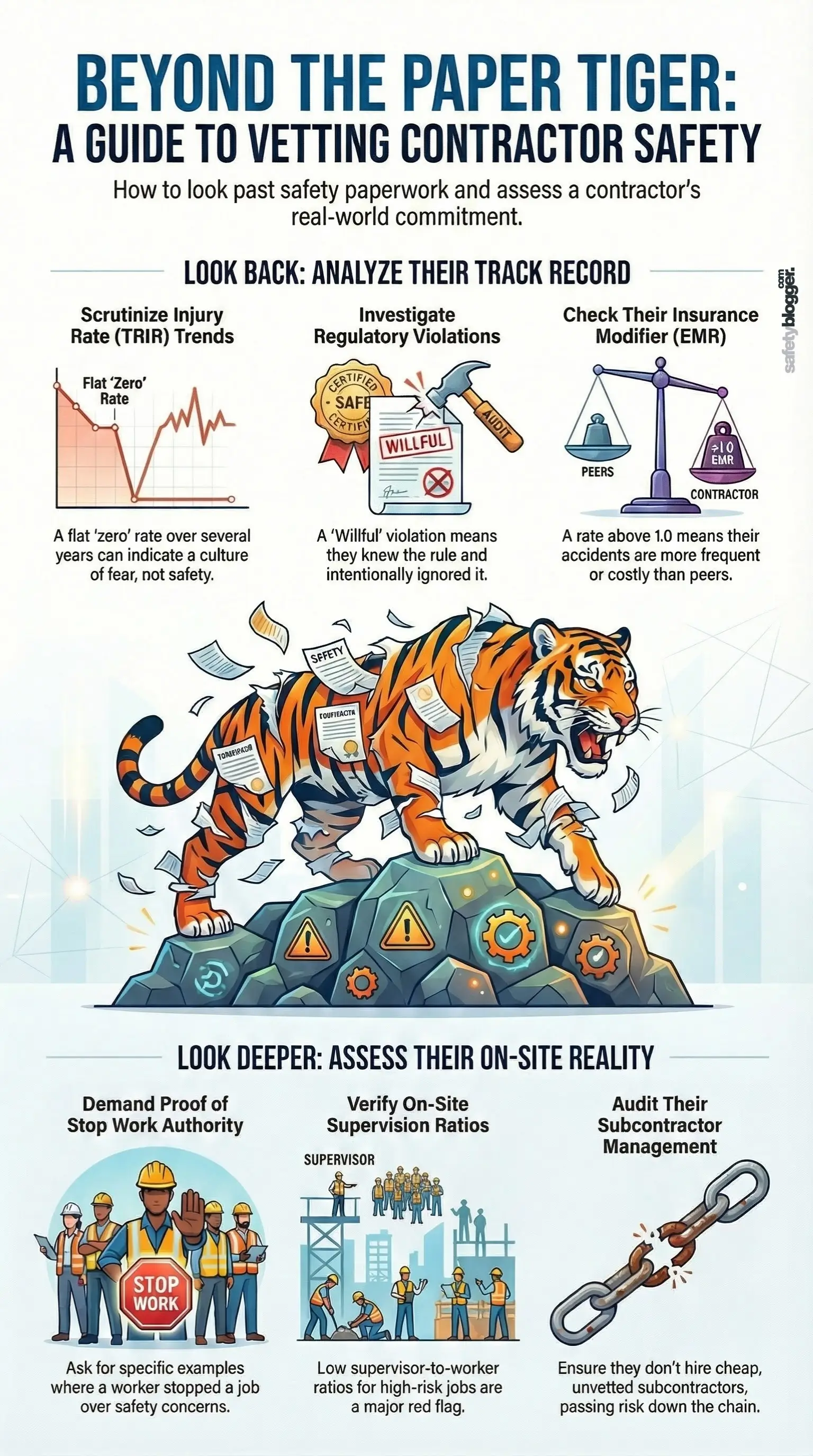

TRIR is the standard metric for measuring safety performance, but a single number (e.g., "0.5") is meaningless without context. You must look for stability and honesty in the data. A contractor who claims "Zero Harm" for five years in a high-risk trade is often hiding injuries to protect their commercial eligibility.

Three-Year Trend Analysis: Look for a downward or stable trend over 36 months. A sudden spike indicates a loss of control, while a flat "0.00" often indicates a culture of fear where reporting is discouraged.

Industry Benchmarking: Compare their rate against the specific industry average (e.g., NAICS code). A painting contractor should have a lower rate than a steel erection company; if the steel erector is lower, verify their reporting integrity.

Severity Potential: Analyze the nature of the recordable incidents. A high frequency of minor cuts is better than a low frequency of "near-fatal" incidents that were just lucky.

Case Management Ethics: Check if they aggressively classify incidents as "First Aid" to avoid recording them. Look for injuries that required prescription painkillers or rigid immobilization but were not recorded—this is fraud.

2. Experience Modification Rate (EMR)

The EMR is an insurance benchmark used primarily in North America that compares a company's worker compensation claims against the industry average of 1.0. It is a direct reflection of the financial severity of their accidents.

The "1.0" Threshold: An EMR below 1.0 suggests the contractor is safer than their peers. An EMR above 1.0 means they have had more frequent or more expensive claims, signaling higher risk.

Lagging Nature: Remember that EMR is a "lagging" indicator that looks back 3 years. A contractor might have improved significantly since their last big claim, or they might have gotten worse.

Claims Management vs. Safety: Be wary of companies with a low EMR but high injury rates; this means they are experts at fighting insurance claims in court, not necessarily preventing accidents in the field.

Size Bias: Small contractors can have their EMR wrecked by a single accident. For smaller firms, use EMR as a discussion point rather than an automatic disqualifier.

3. Regulatory Citation History

Government bodies (OSHA, HSE UK, EPA) keep public records of violations. Unlike internal reports, these cannot be sanitized by the contractor’s marketing team. A history of citations reveals a defiance of the law.

Willful vs. Serious: Distinguish between administrative errors and "Willful" violations. A "Willful" violation means they knew the rule and intentionally ignored it—this is a culture killer.

Repeat Offender Status: Look for patterns. If they have been fined three times for "Lack of Fall Protection" in different years, they have a systemic failure in supervision that training hasn't fixed.

Abatement Evidence: Do not just look at the fine; look at the response. Did they contest the fine and lose? Or did they accept it and implement a massive overhaul of their safety program?

Geographic Scope: Check records across all states or regions where they operate. A contractor might be clean in your state but have a terrible record in a neighboring jurisdiction.

Operational Competency (Field Capability)

This section answers the question: "Can they actually do this specific job without hurting anyone?" Generic safety manuals are useless here.

4. Specific Hazard Experience

Experience is not transferable across different hazard types. A contractor excellent at building residential housing may be completely incompetent in a live gas plant or a deep underground mine. You need proof of relevant high-risk exposure.

Similar Scope Verification: Demand evidence of three previous projects with identical hazards (e.g., H2S, high voltage, deep excavation). Generic "construction" experience is not enough.

Method Statement Quality: specific details in their proposed Method Statements. If they copy-paste generic text (like mentioning "roofs" for a trenching job), they haven't planned the work.

Specialized Equipment familiarity: Ensure they have owned and operated the specific safety gear required (e.g., breathing apparatus, rescue tripods) rather than renting it for the first time on your job.

Reference Checks: Call their previous clients and ask specifically about their handling of high-risk permits. Did they follow the rules when the schedule was tight?

5. Verification of Competency (VoC)

Certificates can be bought or forged; true competency must be demonstrated. You need to ensure that the welder, the rigger, and the crane operator actually possess the skills the certificate claims they have.

Practical Assessments: Does the contractor have an internal process to test a worker's skill before they start? Ask to see the scoresheets for their heavy equipment operators.

Assessor Qualifications: Who is signing off on the competency? It should be a Subject Matter Expert (SME), not just an HR administrator ticking a box.

Recency of Experience: A crane license might be valid for 5 years, but if the operator hasn't sat in a cab for 4 years, they are a risk. Check for continuity of work history.

Short Service Employee (SSE) Program: Look for a formal mentorship program where new hires are visually identified (e.g., green hard hats) and supervised more closely for their first 6 months.

6. Equipment Maintenance & Asset Integrity

Old equipment isn't necessarily bad, but poorly maintained equipment is a fatality waiting to happen. The condition of a contractor's tools is a direct reflection of their respect for their workers.

Maintenance Logs: Request the last 6 months of maintenance records for the specific major plant (cranes, excavators) they intend to mobilize. Look for gaps or "missing" months.

Pre-Mobilization Inspections: Do they have a third-party inspection certificate for all lifting gear and pressure vessels? Is it current and valid for your jurisdiction?

Daily Checklists: Audit their "Daily Pre-Start" books. If every checklist is ticked "Safe" with no defects ever noted, the operators are "pencil-whipping" the forms (faking the inspection).

Defect Rectification: Look for proof that reported defects were actually fixed. A checklist noting "leaking hydraulic hose" is useless if the next day's sheet doesn't show it was repaired.

7. Supervision Ratios

Safety lives and dies at the frontline supervisor level. If a contractor under-bids by reducing supervision, they are leaving the workforce leaderless and vulnerable to error.

Risk-Based Ratios: The ratio must match the risk. High-risk activities (Confined Space, Diving) require a 1:1 or 1:5 ratio. Low risk (painting, cleaning) can handle 1:10 or 1:15.

Working vs. Non-Working: Clarify if the supervisor is a "Working Foreman" (hands on tools) or a "Non-Working Supervisor" (hands off). For critical lifts or hot work, you need a Non-Working supervisor who is 100% focused on oversight.

Supervisor Competency: The supervisor must have safety training (e.g., OSHA 30, IOSH Managing Safely), not just technical trade skills. They need to know how to enforce rules.

Span of Control: Ensure the ratio accounts for geography. One supervisor cannot effectively watch ten workers if they are spread across three different floors or widely separated areas.

Systems & Culture (Behavioral Maturity)

This is the "soft" science that prevents the "hard" accidents. It reveals if safety is a core value or just a priority that shifts when money is tight.

8. Subcontractor Management

The "Sub-Sub" trap is a common cause of project failure. You hire a Grade A contractor, they hire a Grade C sub, and the Grade C sub hires casual labor with no training. You must control this chain.

Declaration of Subs: The bid must list all intended subcontractors. Any "To Be Determined" slots are a red flag for future cost-cutting.

Flow-Down Requirements: Verify that the main contractor legally binds their subcontractors to the same HSE standards (and penalties) as the main contract.

Vetting Process: Ask to see the main contractor’s audit of their subcontractor. Did they actually visit the sub's yard, or did they just email a questionnaire?

Right to Reject: Include a clause that gives you, the client, the final right to approve or reject any subcontractor before they step foot on site.

9. Leading Indicators & Reporting Culture

I judge a contractor not by how few accidents they have, but by how many problems they find and fix before an accident happens. This requires a culture of psychological safety.

Near Miss Volume: A healthy culture generates a high volume of Near Miss reports. If a contractor has 100 staff and zero near misses, their people are either blind or scared to speak up.

Hazard Observation Participation: Look for metrics showing that participation is spread across the workforce, not just done by the safety officer.

Closure Rate: Reporting is useless without action. Check their "Time to Close" metric. Do they fix reported hazards within 24-48 hours, or do items sit open for months?

Positive Reinforcement: Does the contractor have a recognition program? I want to see proof that they reward workers for "Good Catches" rather than just punishing them for violations.

10. The "Bridging Document" Capability

When two companies meet, their safety systems collide. The Bridging Document is the diplomatic treaty that decides whose rules apply. A contractor who doesn't understand this is a liability.

Gap Analysis: The contractor must be able to identify where their procedures differ from yours (e.g., "Our lock colors are different") and propose a solution.

Primacy of Rules: Explicitly agree on whose Permit to Work (PTW) system governs the site. Ambiguity here leads to unauthorized work.

Emergency Response Interface: How will their team contact your emergency services? Do their radios talk to your control room? This must be mapped out before mobilization.

Training Alignment: If your site requires specific training (e.g., H2S Alive), the bridging document must confirm the contractor accepts this as a prerequisite for entry.

11. Stop Work Authority (SWA) Evidence

Every contractor puts "Safety First" on their website. I need to know if a 20-year-old apprentice has the confidence to stop a 50-year-old superintendent from doing something stupid.

Documented Examples: Ask for three specific case studies where work was stopped for safety reasons. If they can't provide them, SWA is likely just a slogan.

Management Support: Look for evidence that management backed the worker who stopped the job, even if it turned out to be a false alarm.

Restart Protocols: How do they restart after a stop? There should be a formal verification process to ensure the hazard is cleared, not just a verbal "get back to work."

Training Saturation: Verify that SWA is part of their induction for every employee, not just the safety team.

The "Hidden" Business Risks

Safety is expensive. Financial distress or ethical rot in a company will always manifest as a safety failure on the job site.

12. Financial Stability & Turnover

A desperate contractor is a dangerous contractor. When cash flow is tight, maintenance is skipped, training is cancelled, and pressure is applied to the workforce to rush.

Employee Turnover Rate: High turnover means you are constantly dealing with "green" hands who don't know the site hazards. A stable crew is a safe crew.

Payment History: Check if they pay their suppliers and subcontractors on time. If they are stiffing their scaffold supplier, that supplier might pull the gear (or provide junk) in the middle of a job.

Credit Rating: A quick financial health check can predict safety performance. If they are near bankruptcy, they will cut every corner possible to survive.

Resource Availability: Ensure they actually own the resources they bid. If they are relying on "just-in-time" hiring for the project, you risk significant delays and competency gaps.

13. Welfare and Labor Rights

How a company treats its lowest-paid worker is the truest test of its culture. You cannot expect high-performance safety from a worker who is hungry, exhausted, or living in squalor.

Living Conditions: If the project involves a camp, audit it. Look for overcrowding, hygiene issues, and food quality. Poor welfare spreads disease and lowers morale.

Fatigue Management: specific policies on working hours. Do they strictly enforce a maximum 12-hour shift? Do they mandate rest days?

Transportation Safety: Check the buses or vehicles used to transport staff. Are they roadworthy? Do they have seatbelts? Many industrial fatalities happen during the commute.

Grievance Mechanisms: Does the workforce have a way to complain about unfair treatment without fear of deportation or firing? A suppressed workforce will never report safety hazards.

14. Incident Investigation Maturity

You want a contractor who learns from mistakes, not one who hides them. Their investigation reports will tell you if they are interested in root causes or scapegoats.

Root Cause Methodology: Do they use a recognized system like TapRooT, ICAM, or 5 Whys? "Worker didn't pay attention" is not a root cause; it's a cop-out.

Systemic vs. Behavioral: Look at their corrective actions. If 90% of their actions are "Retrain Worker" or "Disciplinary Action," they are failing. Good actions involve engineering controls or system changes.

Lateral Learning: Do they share lessons learned from one site to another? Ask for a "Safety Alert" they issued company-wide after an incident.

Transparency: Are they willing to share redacted reports from other clients? A contractor who says "That's confidential" often has something to hide.

15. The "Bait and Switch" on Key Personnel

This is the oldest trick in the book. They win the bid with the CV of a "Superstar Safety Manager," then move him to another project and send you a rookie.

Contractual Locking: Name the Key Personnel (Project Manager, HSE Manager, Superintendent) in the contract. Make them "Essential Personnel."

Replacement Penalties: Include a clause that requires your written approval for any replacement, and potentially a financial penalty if they swap key staff early in the project.

Interview Rights: Reserve the right to interview and veto the proposed replacement. The new person must have equal or better qualifications than the original.

Onboarding Overlap: Demand a mandatory handover period (e.g., 2 weeks) where both the outgoing and incoming manager are on site to ensure continuity of safety leadership.

Comments

Loading...